Building Capacity in a Pandemic: An Alternate Staffing Model

COVID-19 erupted across the nation putting unprecedented stress on hospitals. In mid-March 2020, statistical models from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington in Seattle projected Connecticut’s need for more hospital beds during the pandemic’s peak, prompting Governor Ned Lamont to request hospitals increase bed capacity by 50% (Putterman & Brindley, 2020). At Yale New Haven Hospital (YNHH), a 1,541-bed academic medical center in New Haven, scenario planning for COVID-19 indicated the need for 500 additional beds.

In addition to needing more nurses, hospital leaders realized the intensive care unit (ICU) and medical-surgical care models were not aligned with COVID-19 workflow. Wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) for entire shifts, using new policies and guidelines and minimizing multiple caregivers entering and exiting negative pressure rooms required a different approach to care delivery. For two decades YNHH used a primary nursing model to provide patient care, which enables patient-centered nursing practice (Wessel & Manthey, 2015). Team nursing, often used during nursing shortages, originated following a World War II nursing shortage. Team nursing also was more popular after a dramatic increase in technological advancements put a strain on traditional nursing models. Team nursing allows for clinicians with varying skill levels to collaborate in providing patient-centered nursing care (Sherman, 1990). In a pandemic when nursing resources are limited, this concept was a viable option.

Strategy for ICU staffing

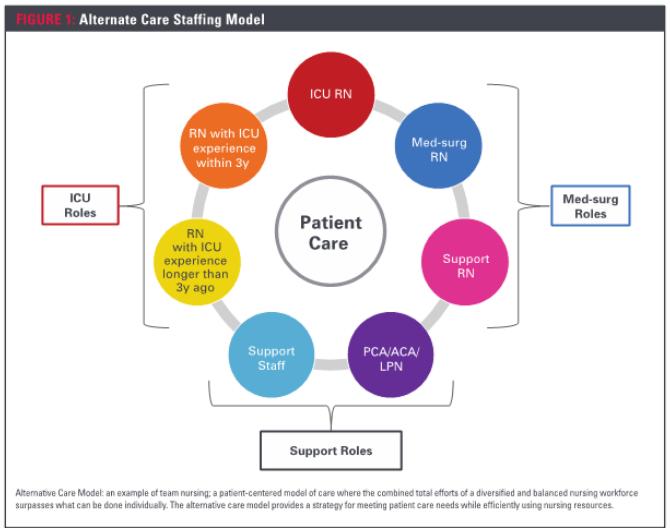

Pre-COVID-19, the YNHH adult ICU capacity included 193 beds across 11 adult ICUs staffed with 550 employed critical care nurses regularly scheduled for full-time, part-time and casual positions. YNHH increased ICU capacity by 75% to a potential 338 beds by converting general patient care units and perioperative spaces to ICUs, resulting in greater demand for critical care nurses. Expected treatments for COVID-19 require 1:1 nurse-to-patient staffing, further widening the resource gap and making it necessary to maximize the use of this highly specialized nursing workforce. The expected peak of the COVID-19 pandemic was imminent. Nurse leaders made the decision to use existing organizational capacity to bridge the need for resources, expanding the ICU nurse’s ability to care for a larger number of patients using a nursing team support model (Figure 1).

A planning team with representation from multiple service lines and front-line members including staff nurses, nursing professional governance and education convened to address the anticipated ICU resource availability gap. The contingency plan was established using a combination of the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s report (Halpern & Tan, 2020), which recommends a tiered approach to pandemic staffing and the concept of team nursing. The YNHH alternative staffing model was designed to use all organizational resources available to manage the anticipated volume and maintain the highest level of quality care to all hospital patients.

The model consisted of several unique features to ensure adequate resources and support for staff caring for COVID-19 patients. First, the alternative care model minimized use of PPE and maximized support to individuals directly caring for patients. Secondly, the model provided support in the event the standard model of staffing would need to be modified if volume became overwhelming. Thirdly, ambulatory nurses, care associates, technicians and other clinical and non-clinical staff, from procedural and ambulatory locations were well suited to provide much needed inpatient support. Although eager and ready to assist, these employees needed to be retrained or newly educated for their assignment. Staff were identified, received education and were redeployed via the YNHH labor pool into care delivery models maximizing the capabilities and skills sets of all team members. This model also ensured preservation of nursing resources for the practice of nursing including assessment, planning, intervention and evaluation.

In addition to existing staff, nursing students from affiliated programs completing clinical rotations were hired as student nurse technicians allowing them to provide support to the nurse in an unlicensed role and then transition into a graduate nurse position after graduation.

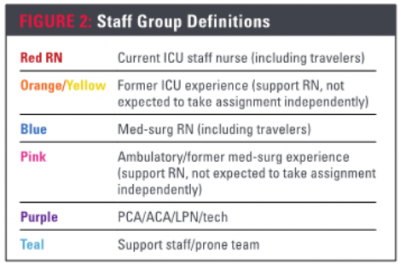

In the initial phase of planning, nursing management completed an inventory of nurses in non-inpatient settings such as ambulatory clinics and procedural areas, in addition to nurses working in non-direct care roles such as clinical informatics. The inventory included information about clinical background, previous specialty/area worked and number of years since practicing at the bedside. Nurses were stratified into groups based on how quickly they could be safely retrained and redeployed to the inpatient setting. A color-coded system was developed to expedite appropriate placement of nurses in the correct resource group and to safely re-deploy them (Figure 2). Leaders assumed nurses who practiced in critical care within the past 12 months would require the least amount of retraining before caring for patients in the ICU. They were offered time to re-familiarize themselves with clinical areas and were often deployed to the ICU where they previously worked.

These nurses became red RNs: a current ICU nurse or one who had practiced in the setting within the past 12 months. Nurses who had worked in an ICU previously but had not practiced in greater than 12 months were the second group to be retrained as support RNs for the ICU nurse. These nurses were categorized into two groups: orange RNs if ICU experience was within the last three years and yellow if ICU experience was greater than three years ago. Orange and yellow nurses were placed in the same category. The support RN was a role created for team members who could not take a full patient assignment, but had vital bedside skills. This distribution of work required transparent conversations at the beginning of each shift to optimize operational strength and performance. Topics discussed were level of clinical expertise, scope of practice and role clarification, and a daily team responsibilities worksheet was created. The filled-out worksheet assigned each team member to certain tasks which allowed for safe distribution of work, collaborative patient care workload and a plan to cluster care.

Strategy for medical-surgical staffing

Nurses with medical-surgical floor experience were stratified in a similar manner so they could support the inpatient unit nurses. The medical-surgical areas utilized the alternative care model with adjusted nurse-to-patient ratios, with a model similar to the one used in the ICU. Blue RNs were current medical-surgical nurses or nurses who had worked medical-surgical nursing previously but had not practiced in greater than 12 months. Nurses away greater than 12 months were retrained and utilized as pink support nurses when nurse-to-patient ratios on the medical-surgical COVID-19 units reached greater than 1:5.

Retraining

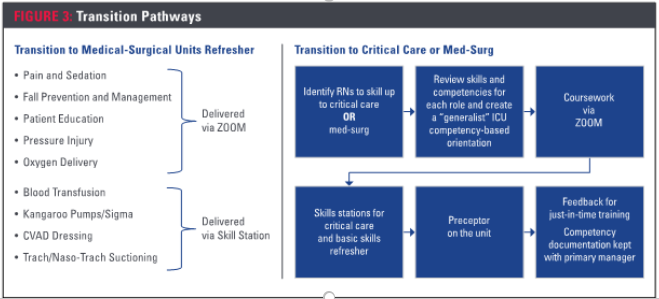

The second phase was retraining of staff. Nurses new to the hospital’s inpatient computerized documentation system enrolled in online courses. Upon completion, the nurse participated in a live video conference overview of inpatient computerized documentation. The centralized nursing education department developed a transition-to-practice refresher for both the ICU and medical-surgical nurses (Figure 3). Content regarding airway management, medications and dysrhythmias were offered in classes via a video conference. Specific skills were reviewed using live education. After completing the training, nurses were directed to the labor pool responsible for centralized nurse staffing resources. The nurses received a competency-based orientation manual, name of their preceptor and assignment to a unit for a minimum of two 12-hour shifts of orientation. The nurses were then provided schedules and were deployed daily based on their assigned role and specialty.

Staff deployment

It was determined assigning nurses consistently to the same unit provided many benefits. Managers were able to incorporate nurses from the labor pool into their schedules, allowing for easier adjustment to inpatient care and the opportunity to bond with the units’ patient care team. Half of the critical care nurses, consisting mostly of red and orange nurses, were pre-assigned to the COVID-19 ICU. The remaining critical care nurses in the labor pool, or the yellow support nurses, were deployed each shift to support units implementing the alternate care model.

At the peak of the hospital’s COVID-19 census, 26 of the 80 inpatient units were COVID-positive and four were mixed with COVID and non-COVID patients. Workflow was more complex on these units and most of the blue and pink nurses were pre-assigned to help support nurses in caring for these patients. The remaining medical-surgical labor pool nurses were deployed each shift based on unit staffing needs.

Clinical staff from departments with low patient volume such as the operating room, procedural areas and rehabilitation were able to be redeployed to support patient care, but were not given patient assignments. These employees were color-coded as teal and some were assigned to the proning/support team.

Proning team

Proning is a technique of positioning a patient face down to facilitate pulmonary functioning. Proning the ventilated patient, usually sedated and immobilized, required a team of four or more caregivers to safely reposition the patient while maintaining the airway and ensuring the vent tubing remained intact, thus preventing unnecessary exposure to aersolization.

The proning team was trained on how to correctly prone and a schedule was made for a four-to-six member team available 24/7. The ICU nurses would request the proning team to a particular room using a hospital-issued mobile device. When not directly involved with proning, the team functioned as part of a support team. The team’s activities included bathing, patient transport, bringing supplies and equipment to patient rooms and running off-unit errands, such as retrieving units of blood.

Opportunities and challenges

During the initial inventory of nurses, leaders found no database existed listing YNHH nurses with past critical care or medical-surgical experience. The hospital relied on leaders from multiple locations to send information, resulting in a less than optimal process.

Resources were required to assist in the retraining process, including educators with various areas of expertise. Centralized nursing education department specialists developed competency-based orientation manuals for each role and designed both in-person and video training programs for each of the specialties. A large number of nurses reported to the labor pool for orientation information, assignment and scheduling during a time of required social distancing, which prompted the need for pre-assignment. Once pre-assigned, nurses reported directly to their assigned units, bypassing the labor pool office.

Scheduling presented a challenge as most redeployed nurses were accustomed to working an ambulatory day shift schedule Monday through Friday. Supporting the inpatient setting required rotating shifts and weekends. The first schedules were unbalanced with the majority of nurses working the day shift, requiring many to move to nights.

Lessons learned

Increasing the workforce during the pandemic required innovative thinking, collaboration, rapid planning and effective execution. A COVID-19 resurgence remains uncertain, requiring ongoing readiness. AT YNHH, the following factors need to be maintained and fostered to provide care:

- The ability to leverage the strengths and abilities of all team members, giving everyone an opportunity to contribute.

- An agile and flexible nursing workforce is key. We are evaluating how to best ensure our non-inpatient nurses retain their newly refreshed skills and competencies.

- Ongoing communication and engagement with our teams will foster the newly formed partnerships among nurses in our organization and strengthen our team for whatever we may face in the future.

- An increased sense of teamwork among all specialties, departments and functions across the organization was developed and will be maintained. This teamwork allowed us to quickly identify issues and respond in a rapid manner to a turbulent situation.

References

Halpern, N.A., & Tan, K.S. U.S. ICU resource availability for COVID-19. Society of Critical Care Medicine. Retrieved from https://sccm.org/Blog/March-2020/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19

Putterman, A., & Brindley, E. (2020, April). Connecticut’s COVID-19 peak could be two weeks away. The state won’t have enough hospital beds or ICU options when that happens, model predicts. The Hartford Courant. Retrieved from https://www.courant.com/coronavirus/hc-news-coronavirus-models-for-connecticut-20200402-kezenlthqfempmpouc6hv2vjjq-story.html

Sherman, R.O. (1990). Team nursing revisited. Journal of Nursing Administration, 20 (11), 43-46

Wessel, S., & Manthey, M. (2015). Primary nursing: Person-centered care delivery system design. Minneapolis: Creative Health Care Management

About the Author

Kelly Poskus, MS, RN, CNRN, is director, nursing-neuroscience services

Jeannette Bronsord, DNP, RN, NEA-BC, is executive director of surgical services

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals at Yale New Haven Hospital for their assistance with this article: Ena Williams, MBA, RN, CENP, senior vice president and chief nursing officer; Mary Cleary, MSN, RN-BC, manager, core education center, professional practice excellence; and Alyssa Yardis, MSN, RN, CNRN, nursing professional development specialist, neuroscience services.