Creating a Culture of Inquiry: Building from the Inside Out | Compendium 2.0

Chapter Table of Contents

Introduction

Does a Culture of Inquiry Occur Spontaneously?

Operationalizing a Culture and Climate of Inquiry

Sustaining Positive Experiences of a Climate of Inquiry

Three Strategies in Creating a Culture of Inquiry

Interview Results: Nurse Managers on Creating a Culture of Inquiry

Thinking Framework Methods and Tools for Each Approach

Conclusion

About the AONL Culture of Inquiry Committee

Appendices

References

1. Introduction

The Culture of Inquiry committee explored what leadership should prioritize — organizational culture — and how the workforce should experience the work environment, or in other words, the organizational climate necessary for creating a culture of inquiry. According to Joseph, Kelly, Davis, Zimmermann and Ward (2023), organizational culture comprises shared values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors that guide how members interact and approach work. In contrast, organizational climate is the perception or mood of the workplace atmosphere.

The committee interviewed nurse managers who lead the councils within professional governance structures (see Table 1). These leaders were well-positioned to understand organizational expectations for questioning the status quo, challenging norms, driving innovation and identifying both barriers and solutions. Their examples demonstrated how communication, curiosity and monitoring behaviors support a culture of inquiry. These findings validate the model's relevance and its potential to improve organizational culture and outcomes.

2. Does a Culture of Inquiry Occur Spontaneously?

A culture of inquiry does not emerge spontaneously; it must be intentionally cultivated, beginning with the climate of inquiry.

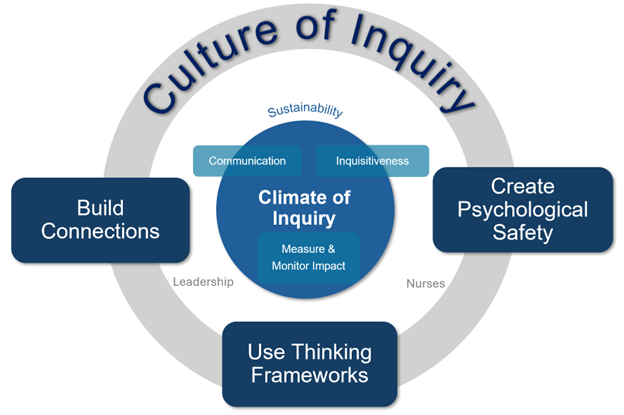

The climate of inquiry represents the psychological and social atmosphere within nursing teams and leadership, influencing how the nursing workforce engages in questioning, learning and innovation. According to the culture of inquiry model (Figure 1), a strong climate of inquiry serves as the foundation for sustainable inquiry practices, shaping the behaviors, norms and professional environment necessary for evidence-based practice, innovation and continuous learning. Organizations can establish a strong foundation before expanding inquiry into broader institutional norms by prioritizing this internal climate. The internal climate of inquiry consists of three core elements: (a) communication, (b) inquisitiveness and (c) the ability to monitor and measure for sustainability. In a culture of inquiry, leadership at all levels should leverage three key strategies: (a) fostering connections, (b) cultivating psychological safety, and (c) utilizing thinking frameworks to shape norms, values and expectations. When these elements and strategies are in place, nurses can communicate openly, ask "why" and "what if" questions, and actively monitor the level of support they feel in their workplaces.

Figure 1: Culture of Inquiry Model

© AONL, 2025

3. Operationalizing a Culture and Climate of Inquiry

A. First Core Element of a Climate of Inquiry: Effective Communication

The culture of inquiry committee conducted interviews that revealed nurse managers were more engaged in professional governance councils when chief nursing executives (CNEs) actively participated, as shown in Table 1. When leaders show they are open to communication, responsive to needs and use an evidence-based approach to making decisions rather than relying solely on authority or tradition, they help create an environment where evidence-based inquiry becomes normalized throughout the organization.

By establishing structured pathways for communication, such as professional forums and digital collaboration platforms, senior leaders help ensure nurses actively express their perspectives.

B. Second Core Element of a Climate of Inquiry: Inquisitiveness

Inquisitiveness is foundational to a climate of inquiry. It is cultivated in the workplace “through social and structural processes to stimulate and nurture communication, belonging, questioning, psychological safety, use of evidence, learning, and innovation" (AONL, 2023). The nurse leader fosters inquisitiveness in their nurses to fuel curiosity.

Interviews with nurse managers highlighted both barriers to, and drivers of, inquisitiveness (Table 1). Lack of responsiveness from senior leaders and nurse managers’ perception that their questions or concerns won't be addressed create significant barriers to a culture of inquiry. When administrators leave survey results unaddressed or overlooked, they may intensify frustrations, negatively affect the work environment and diminish both curiosity and employees' sense of connection. Implicit bias may also hinder one's ability to be inquisitive. Luther and Flattes (2022) identified bias as a barrier to team-based functioning and psychological safety, which is one of the essential components of a culture of inquiry.

Nurse leaders must consider how their interactions with nurses promote or unconsciously impede potential connections. Leaders may be able to overcome bias through introspection, exploring their personal beliefs and identifying their "blind spots." They may also implement inclusive and evidence-based communication strategies (Edgoose et al., 2019) or advocate for organizational bias education.

When nurses believe their questions and concerns will be addressed, they are more likely to ask questions. This ultimately helps nurse managers connect with their teams, supports psychological safety and stimulates inquisitiveness. In our interviews with nurse managers, they cite approachability, availability and openness to dialogue as leadership qualities that foster their inquisitiveness. This positive reinforcement pattern stands in contrast to the barriers mentioned earlier, where ignored feedback and unaddressed survey results diminish curiosity and engagement.

When senior leaders address the concerns of nurse managers, they boost nurse managers’ confidence and help them feel validated. This validation, in turn, empowers nurse managers, sparks their inquisitiveness and enhances their psychological safety.

Gray et al. (2024) observed this effect while implementing an interactive training program designed to nurture curiosity and inquiry. Their strategies promoted a questioning attitude, which led to a deeper understanding of issues and supported the Thinking Framework, a strategy that supports a culture of inquiry. Educators and leaders must cultivate inquisitiveness, which is integral to a culture of inquiry. This culture thrives on challenging existing practices and exploring new possibilities. Tools such as the INQUIRE model equip educators and leaders to systematically foster nurses' ability to examine clinical questions and propose evidence-based solutions (Thacker, 2022).

C. Third Core Element of a Climate of Inquiry: Monitoring and Measuring for Improvement

Leaders need robust, reliable measurements to assess if a culture of inquiry can thrive. Organizations can understand their climate by tracking engagement levels, implementing structured inquiry practices and linking inquiry efforts to broader quality metrics — such as patient outcomes and care effectiveness. Measurements help to validate the culture of inquiry and highlight its alignment with a broader commitment to safety, accountability and organizational excellence. Leaders should incorporate research-backed measures to evaluate psychological safety, leadership responsiveness, engagement and inquiry processes. The appendices provide relevant tools for assessing behaviors and communication (Appendix A), inquiry and collaboration (Appendix B) and accountability (Appendix C).

4. Sustaining Positive Experiences of a Climate of Inquiry

Nurses and nursing leaders at all levels can shape and sustain a culture of inquiry. How they relate to and support each other affects a workplace’s perceived mood and atmosphere. Once they establish a stable and engaged climate of inquiry, their next step is to expand outward to embed inquiry into a broader institutional culture.

To survive long-term, a culture of inquiry depends on ongoing organizational commitment and systems that consistently support nurses’ inquisitiveness. For example, nurses need regular training and education to maintain and improve their inquiry skills throughout their careers. Leaders should prioritize creating a safe environment where staff feel comfortable speaking up without fear of negative consequences or reprisal. Organizations must establish effective communication channels that allow for meaningful responses to questions. Additionally, structured methods for asking and addressing inquiries can help make these practices a part of the organizational culture. By prioritizing the internal environment — strengthening the climate of inquiry first — organizations create the foundation for a culture that fuels evidence-based decision-making, professional growth and excellence in patient care.

5. Three Strategies in Creating a Culture of Inquiry

Leaders influence culture by shaping expectations, modeling behaviors and providing necessary resources. The following elements are pillars of the Culture of Inquiry Model: 1) building connections, 2) establishing psychological safety and 3) applying thinking frameworks.

Strategy No. 1: Build Connections

When nurse leaders build strong connections with their teams, they create environments where staff feel empowered to question practices, share ideas and collaborate on improvements. These connections create the foundation for psychological safety and trust, conditions that are necessary for a culture of inquiry to thrive.

Leaders can cultivate meaningful connections through conversations, gestures and consistent engagement with their teams. These interactions include both verbal communication (tone and word choice) and nonverbal cues (body language, facial expressions and eye contact). Leaders who practice active listening, provide affirmation, and demonstrate sincerity foster mutual respect and build trusting relationships (Huber & Joseph, 2022). Leaders must go beyond forming relationships to create inclusive environments where everyone feels valued, respected and able to contribute. Leaders who combine inclusive practices with structural and psychological empowerment frameworks create conditions for innovation through improved team dynamics and cross-pollination of ideas (Kanter, 1993; Spreitzer, 1995).

Using Spreitzer's psychological empowerment framework (2017), nurse leaders can significantly enhance team connections and innovation. Spreitzer's framework is unique because it incorporates leaders' practices with their staff's perceptions and thoughts about the work environment. This approach resonates with nurses based on the challenges and demands of the profession. The four core tenets of the psychological empowerment framework are meaning, competence, self-determination and impact. They serve as the foundation for building strong relationships and creating a positive work environment (Spreitzer, 2017).

Nurse leaders also can build strong connections by creating a shared sense of purpose that helps nurses find personal meaning in their work (Taplin, 2024). By investing in professional development and fostering competence, leaders build trust and mutual support and can create a cycle for continuous learning. Transparent communication channels can create feedback loops, so nurses feel heard and valued, fostering open dialogue. Bidirectional, open communication builds trust within the team and encourages collaboration, as nurses feel confident in sharing their ideas and concerns. Additionally, recognizing and celebrating the impact of nurses' contributions can strengthen their motivation and help to reinforce a positive, innovative work environment. By acknowledging and valuing each nurses’ efforts, leaders can create a supportive atmosphere encouraging continuous improvement and shared dedication to patient care excellence.

Connections and innovation are pivotal in shaping work environment structures, which in turn influence factors such as control over professional nursing practice and job satisfaction (Laschinger & Havens, 1996). Kanter's theory of structural empowerment emphasizes that when nurses have access to the necessary resources, support and opportunities for growth, the nurturing environment will help inquisitiveness and collaborative problem-solving thrive (Kanter, 1993). Additionally, Kanter's theory suggests that nursing leaders who facilitate open communication and foster staff support networks may create stronger connections and enable more innovative and resilient teams. A structural foundation is critical for establishing trust and mutual support between team members (van Dyk, et al., 2021).

When combined, Spreitzer and Kanter’s models create a comprehensive approach to empowering teams by addressing nurses' structural and psychological needs. A holistic empowerment strategy promotes a positive work environment where nurses feel connected and motivated to innovate.

Recent publications discuss the balance of collectivism and individualism and their relationship with innovation, finding that encouraging individual creativity and initiation within a collectivist framework can lead to a more dynamic and innovative environment (Lee & Seo, 2024). Building strong connections between team members helps create equilibrium. Leaders should value collective efforts and individual contributions while recognizing potential drawbacks of collectivism, such as groupthink and resistance to change. When nurse leaders acknowledge and support collectivist principles, mutual support, empathy and shared responsibility can follow. A positive work environment can boost job satisfaction, motivation and team cohesion. It is essential to understand that the effectiveness of leaders may differ depending on the collectivist values of individual nurses (Lee & Seo, 2024).

Building connections also promotes involvement, ensuring varied relationships (Gong, Liu, Rong, & Fu, 2021). Nursing leaders who advance inclusive practices help amplify multiple perspectives and deepen connections with their teams. Together, a nurturing environment for innovation through enhanced team dynamics is created. Integrating a systems perspective also helps build relationships and interconnectedness within health care, leading to more holistic and sustainable solutions (Gee, et al., 2022). An environment that values connections, inclusion and a unified approach is more likely to sustain innovation long-term, continuously supporting and leveraging the strengths of all its members. Connections create meaningful and valuable relationships that can provide support, opportunities and a sense of belonging. These connections can be the foundation for collaboration, innovation and personal growth (van Dyk, et al., 2021).

Strategy No. 2: Establish Psychological Safety

Psychological safety within a team is defined as “a shared belief that team members will not face rejection or embarrassment for sharing ideas, questions, and concerns” (Bresman & Edmonson, 2022). Psychological safety contributes to workplace productivity and team innovations and promotes feelings of inclusion, trust and belonging (Edmondson & Bransby, 2023; Ito et al., 2022; Akkoc, 2022). Clark (2020) expands the conceptualization of psychological safety with his building-block, four-stage model: (1) inclusion safety (feeling accepted), (2) learner safety (asking for help), (3) contributor safety (volunteering ideas) and (4) challenger safety (questioning others, including those in authority). These stages align with effective communication, inquisitiveness, and behavioral norms essential for creating the foundation for a culture of inquiry. Psychological safety is challenging; team members may not simultaneously be at the same stage. However, it is essential for a culture of inquiry.

The nurse leader is a vital appraiser and facilitator of psychological safety at the team level and in shaping team behaviors. They must also have their own sense of psychological safety. The AONL Joslin Insight survey (2025) indicates that 73% of nurse leaders reported incivility as the most frequent factor impeding their sense of psychological safety, followed by 48% who cited a lack of leadership or colleague support. This underscores the importance of nurse leaders at all levels in creating safe spaces to learn, where team members are supported and can contribute to the success of an organization (Brown, 2021). When a person’s psychological safety deteriorates or is compromised, there is a fear of retaliation, damaged integrity, stagnated creativity and suppressed ideas. A disrespectful interaction can result in a “disproportionately toxic impact on engagement and belonging” (Gube & Hennelly, 2022). Psychological safety is a fundamental human driver for motivation and is supported within Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, emphasizing a desire for security and safety, belongingness, and esteem/accomplishments. Psychological safety is essential to promulgate integrity, innovation, and inclusion and is the foundation for organizational resilience (Gube & Hennelly, 2022).

Actionable Ways to Empower Nursing Teams

To empower their teams, nurse leaders first need to create psychologically safe environments. By fostering trust, inclusivity and open communication, leaders can ensure that every team member feels valued, supported and confident in contributing ideas or raising concerns. Below are actionable strategies to achieve this goal:

- Communicate with civility and transparency, ensuring receptivity to feedback; leaders empower confidence by encouraging and engaging in honest and nonjudgmental conversations. Align words with actions to empower confidence.

- Define expectations for ethical decision-making and integrity; taciturn and vague expectations can have consequences.

- Structure meetings with clear goals, invite a range of perspectives and ensure authentic communication through active listening.

- Ask open-ended, shared-ownership questions to reduce barriers and promote inquiry. Examples include: “What do you hear about X?,” “How can I help?” or “What did I do to put you into this challenging situation?”

- Develop a safe, accessible process for raising concerns and ensure team members know how to use it.

Promote teamwork using tools such as TeamSTEPPS or CREW Resource Management and encourage innovative thinking. - Use motivational, empathetic and meaning-making language to inspire behavior change and inclusivity.

- Allow risk-taking and support learning from failure without fear of judgment or negative consequences.

- Provide consistent access to information, resources and opportunities to empower front-line leaders and nurses.

Senior leaders must ensure that the entire workforce (nurse managers, nurses and support staff) feel comfortable expressing concerns, challenging the status quo and engaging in problem solving without fear of reprisal. Interviews with nurse leaders indicated that front-line staff often hesitate to speak up due to a lack of transparent follow-up processes or concerns that their input will be ignored. When inquiries and feedback do not lead to visible action, engagement declines and skepticism toward leadership grows. However, when leaders acknowledge concerns and make small changes — such as improving workflows or addressing environmental barriers — they strengthen trust, demonstrating and reinforcing the value of inquiry.

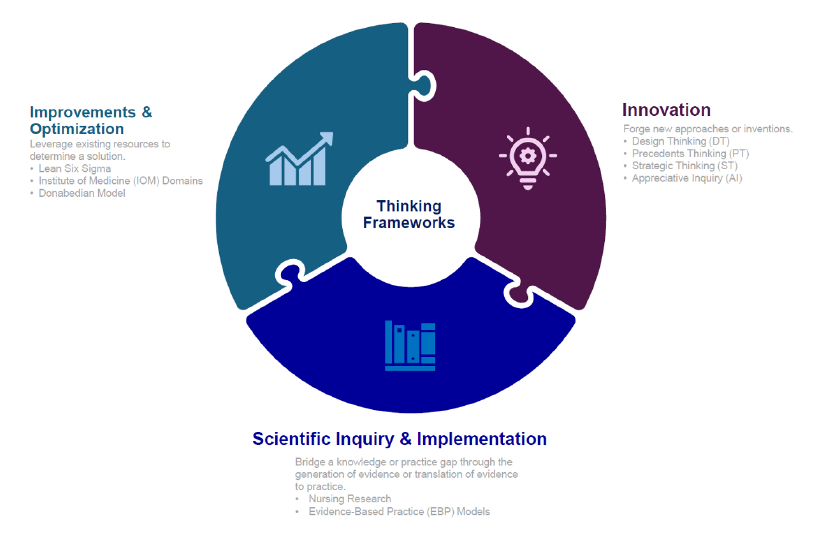

Strategy No. 3: Apply Thinking Frameworks

While there are a variety of approaches that nurse leaders can take to tackle complex problems, structured thinking methods give nurses a reliable roadmap for solving them. They offer clear guidelines about both how to think about problems and what actions to take to address them.

The frameworks are built upon a foundation of processes, principles and procedures, all working harmoniously to drive change. These thinking frameworks support psychological safety and connection building — keys to a culture of inquiry. With these frameworks, nursing teams can solve problems methodically, collaborate across disciplines, work better with other departments and develop person-centered solutions that improve care delivery.

As health care becomes increasingly complex, it requires nurses to move beyond traditional, experience-based decision-making and toward more systematic, evidence-based approaches.

The U.K.’s Design Council Framework, particularly the Double Diamond methodology, provides a human-centered, iterative process emphasizing divergent (broad exploration) and convergent (focused action) thinking to identify, define and address challenges (Lewrick et al., 2018).

The Interdisciplinary Learning and Innovation Process fosters psychological safety, open communication and co-creation. This process encourages collaboration through workshops or maker spaces, enabling nurses to partner with health care professionals to develop solutions such as improved devices and streamlined workflows (Elsayed et al., 2023; Nelson, 2020; American Nurse, 2025).

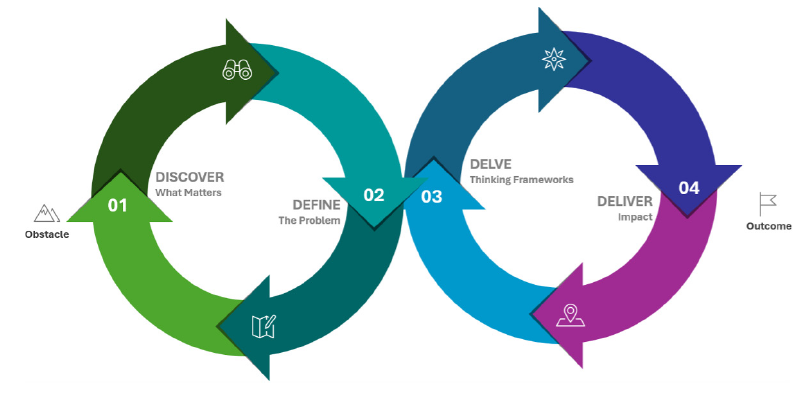

The Infinite Loop Inquiry Process (Figure 2) has four key phases that combine the divergent and convergent thinking styles of the Double Diamond with the communication and collaboration of the Interdisciplinary Learning and Innovation Process. Nurses and nurse leaders move non-linearly through these phases, revisiting earlier stages when they receive feedback or gain new insights.

Figure 2: Infinite Loop Inquiry Process: Four Steps of Inquiry

Process adapted from the Double Diamond Design Council (2025).

Teams must iterate through the Infinite Loop Inquiry Process to improve their solutions with each attempt. Its phases, which are based on two types of thinking, are as follows:

- The Discover Phase (Divergent thinking): Nurses identify the problem by engaging with those affected and gathering insights from patients, families and teams to uncover unmet needs or systemic issues.

- The Define Phase (Convergent thinking): Nurses synthesize insights from the discovery phase to clearly redefine the challenge.

- The Delve Phase (Divergent thinking): Nurses generate solutions using the most suitable thinking framework — improvement, scientific inquiry or innovation. Leaders should support diverse approaches and provide necessary resources.

- The Deliver Phase (Convergent thinking): Nurses take key actions to implement, evaluate and refine processes, generate knowledge or test prototypes.

Organizations and individuals can cultivate a culture of inquiry by applying diverse thinking and problem-solving approaches. Tables 2, 3 and 4 and Figure 3 outline various thinking frameworks with their focus and implementation methods. Organizations that integrate these frameworks with Interdisciplinary Learning and Innovation Process can create environments where teams feel secure to communicate openly and build connections.

In summary, The Design Council (n.d.) emphasizes leadership and engagement as key drivers of innovation. Nurse leaders who model curiosity, support experimentation and promote participation create environments conducive to inquiry.

When nurses directly involved in patient care participate, they help the organization to develop more practical, workable solutions. Involving patients and families in the process ensures solutions actually address their needs and preferences rather than just organizational priorities.

By integrating the Interdisciplinary Learning and Innovation Process with thinking frameworks, nurse leaders can build psychological safety, strengthen connections and empower nurses.

6. Interview Results: Nurse Managers on Creating a Culture of Inquiry

Nurse managers help create a culture of inquiry but face obstacles that limit engagement and innovation. Table 1 presents challenges and solutions identified through our interviews with these leaders. Source: Nurse Manager Interviews. (2024/2025).

Table 1: Nurse Managers’ Perceived Barriers and Solutions to a Culture of Inquiry

| Experiences | Perceived Barriers | Perceived Solutions |

| Communication | Nurse managers can't see how their input drives change without formal processes to track and follow up on concerns. | Chief nursing executives (CNE) should create a step-by-step path for nurse managers to report problems and get solutions. |

| One nurse manager said their current CNE's refusal to use staff communication tools sends a clear message that she doesn't want to hear from nurse managers. | Administrators should give unit managers notice of significant changes before general announcements to allow them to prepare. | |

| Inquisitiveness | Front-line nurses and nurse managers lose trust and stop speaking up when their concerns get stuck in bureaucracy without clear next steps. | When nursing leaders support staff who speak up, others may infer that speaking up leads to real change, motivating them to raise their concerns. |

| When nurse managers repeatedly raised the same concerns in anonymous surveys month after month, administrators began viewing themselves as "punching bags" while nurses felt unheard. This cycle led to increasingly hostile questions and defensive responses. | Complete the feedback loop by tracking both input (how safe staff feel speaking up) and output (what changes resulted from feedback). Share these metrics with staff to demonstrate the clear connection between speaking up and organizational improvements. This creates a measurable link between psychological safety and actual change, encouraging more staff to provide feedback. | |

| Monitoring | In an extensive health system, system-wide data may be less valuable than department-specific feedback. Nurse managers, especially in small departments, need metrics relevant to their specific areas. | The CNE should report monthly to the nurse management council, addressing the status of council members’ requests and suggestions. |

| Lack of transparency. When administrators focus on selling ideas or controlling the message, they shut down honest discussion. One nurse manager mentioned that staffing incentive changes were announced in a council meeting, leaving her “blindsided,” which became a one-way presentation that left questions unaddressed. | CNEs should engage in two-way discussions about operational impacts before making decisions that impact nurse managers, and ask "Will this positively or negatively impact overwhelmed nurses?" or "Will this change affect nurses working in these conditions?" before making decisions about staffing and resources. |

7. Thinking Framework Methods and Tools for Each Approach

To support a culture of inquiry, leaders can use structured thinking frameworks that provide tools for creative problem solving and innovation. Table 2 outlines different approaches, their purpose and the tools available for implementation.

Table 2: Innovation Thinking Frameworks

| Approach | Focus/Purpose | Methods and Tools | |

| Design Thinking (DT) | Imagine novel solutions and innovations that make a positive impact (Houssaini et al., 2023). | Steps (may vary depending on DT school of thought) and Corresponding Tools (IDEO.org, 2025; Design Thinking Playbook [DTP] 2025; Lewrick et al., 2020) Note: Not all applicable tools for DT are included in this list. | |

1. Empathize/Understand

2. Define

3. Ideate

| 4. Prototype

5. Test

6. Reflect

| ||

| Three Phases of Human-Centered Design (HCD, Wymer et al., 2023) 1. Inspiration 2. Ideation 3. Implementation | |||

| Precedents Thinking (PT) | Combine existing or prior ideas to generate breakthrough innovations (Stefanos & Favaro, 2025). | Three Steps of PT (Istvan et al., 2024) 1. Frame (the challenge) 2. Search (relevant/prior innovations) 3. Combine (pertinent ones) | |

| Strategic Thinking (ST) | Mental disciplines that recognize threats and opportunities, establish priorities, and mobilize a promising path forward (Watkins, 2024). | Five Steps of Reframing a Problem (Binder & Watkins, 2024) 1. Expand

2. Examine

3. Empathize

4. Elevate

5. Envision

| Six Disciplines of ST (Watkins, 2024)

Nine-Step Process for Strategy (Kraaijenbrink, 2022)

|

| Appreciative Inquiry (AI) | Bring people together in narrative-based processes for them to connect openly and honestly and achieve positive change (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005; Van Graas & Gobbens, 2023). | Steps, 4 (or 5) Ds of AI (Sennequier, 2025; Aitken & Hauger, 2025)

| |

Table 3: Improvement and Optimization Thinking Frameworks

| Approach | Focus/Purpose | Methods and Tools | |

| Lean Six Sigma | Eliminate errors and waste in a system and optimize processes (Houssaini et al., 2023). | DMAIC Steps (George et al., 2005)

Tools

| Tools (cont’d)

And others |

| IOM Domains | Use of Six Aims for health care system quality assessment to guide initiatives development. | Institute of Medicine’s Six Domains of Healthcare Quality (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, AHRQ, 2025) | |

|

| ||

| Donabedian Model | Use of three fundamental dimensions in assessing and influencing quality (Voyce et al., 2015). | Three Dimensions

Balancing Measures (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, IHI, 2025) | Seven Pillars of Quality (Schiff & Rucker, 2001)

|

Table 4: Scientific Inquiry and Implementation Thinking Frameworks

| Approach | Focus/Purpose | Methods |

| Nursing Research | Begin with a question and use systematic, scientific inquiry to answer it. Generate new knowledge or validate a theory (Erickson & Pappas, 2020). |

|

| Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) | Provide a process to review, translate and implement research with practice to improve patient care, treatment and outcomes (Dusin et al., 2023). |

And others |

8. Conclusion

Creating a climate of inquiry starts with building a transparent environment focused on open communication, inquisitiveness and measuring results. In such a trusting and engaged system, questions are welcomed, exploration is valued and progress is quantifiable.

When senior leaders model curiosity and encourage open dialogue — and show staff how their input leads to real changes — organizations demonstrate the value of speaking up, as one interview participant noted.

Beyond these foundational elements, senior leaders can sustain a culture of inquiry by encouraging connections among team members, which leads to dialogue and idea exchange. Promoting psychological safety also will ensure that individuals feel secure in voicing their thoughts and challenging ideas. Finally, implementing structured thinking frameworks will equip leaders and teams with tools and methodologies to enhance their analytical and creative capacities.

Together, these components empower organizations to nurture a culture of inquiry.

9. About the AONL Culture of Inquiry Committee

Lead Writers:

M. Lindell Joseph, PhD, RN, editor-in-chief, Nurse Leader; clinical professor and director, DNP and MSN Health Systems/Administration/Executive Leadership programs, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa

Anne Schmidt, DNP, APRN-BC, director, clinical and operational excellence, Optum Advisory, Eden Prairie, Minn.

Committee Members:

David Marshall, DNP, JD, senior vice president and chief nursing executive, Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles, Calif.

Rosanne Raso, DNP, RN, editor-in-chief, Nursing Management; core leadership team, Marian K. Shaughnessy Nurse Leadership Academy; adjunct professor, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University; president, R&R Insights

Maureen Sintich, DNP, RN, executive vice president and chief nursing executive, Inova Health System, Fairfax, Va.

Reynaldo R. Rivera, DNP, RN, director of nursing research and innovation, NewYork-Presbyterian Institute of Nursing Excellence and Innovation; assistant professor of clinical nursing, Columbia University School of Nursing

Cyril T. Amoin, RN, emergency/trauma nurse, Advocate Health Southeast Division

10. Appendices

Appendix A: Measures and Tools to Monitor Behavior and Communication

1. Psychological Safety and Speaking-Up Culture

Team Psychological Safety Scale

Measures: Whether staff feel safe to speak up, share ideas and take risks without fear of retribution.

Relevance: Assesses team-level psychological safety and is widely used in health care to evaluate team dynamics.

Published by: Edmondson (1999)

Just Culture Assessment Tool

Measures: Whether the organization fosters a culture of learning and accountability rather than blame when errors or concerns are raised.

Relevance: Supports psychological safety and a learning culture in high-reliability organizations.

Published by: AHRQ (2017); also see Dekker (2018)

2. Tools to Monitor Behaviors

Self-Assessment Tool: Value-Based Decision-Making

Measures: Alignment of leadership decision-making with values such as integrity, diversity and inclusion, lifelong learning and team leadership.

Relevance: Helps nursing leaders reflect on how their values guide current decisions and identify areas for growth

TeamSTEPPS

Measures: Team communication and coordination in clinical environments.

Relevance: Supports systems-level integration of teamwork and communication practices.

Published by: AHRQ

SCORE (The Integrated, Outcomes-Predictive, Culture and Engagement Survey for Everyone)

Measures: Organizational culture, employee wellness and engagement in a single tool.

Relevance: Offers a holistic view of workforce experience and resilience.

Psychological Safety Index Report

Measures: Four domains—willingness to help, inclusion and diversity, attitude to risk and failure and open conversation.

Relevance: Offers a multi-dimensional assessment of psychological safety within teams.

3. Methods for Team Coordination and Training

Crew Resource Management (CRM) Training

Measures: Team communication, decision-making, situational awareness and other human factors affecting patient safety.

Relevance: Enhances safety and coordination in complex clinical environments by teaching tools like SBAR, briefings, closed-loop communication and stress management.

Motivational Language Self-Assessment Tool

Measures: Leaders' use of motivational language during employee interactions.

Relevance: Helps improve employee retention, motivation and behavior change through better communication.

Reference: Mayfield & Mayfield (2017)

C-Suite Roles and Competencies to Support a Culture of Shared/Professional Governance

Measures: Executive-level behaviors that support shared governance, including staff engagement and alignment with unit leaders.

Relevance: Identifies leadership practices that strengthen empowerment and staff voice across organizational levels.

Published by: Joseph & Bogue (2019); American Organization for Nursing Leadership (AONL Compendium 1.0, 2023)

Appendix B: Surveys and Measures to Monitor Inquiry and Collaboration

1. Inquiry Engagement and Participation

Inquiry Engagement Index

Measures: Composite score that measures how often staff participate in professional governance, research projects, EBP initiatives and unit-based discussions on innovation.

Relevance: Participation in shared governance structures has been linked to higher engagement and improved patient outcomes.

Reference: Gerard, Kazer & Babington (2014)

Idea Submission Rate

Measures: Frequency of front-line staff submitting suggestions for process improvement, research or evidence-based practice initiatives.

Relevance: The ANCC Magnet Model encourages tracking innovation submissions as part of a culture of excellence.

Published by: American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC Magnet Model, 2020)

Participation in Professional Governance Councils

Measures: Attendance and active involvement in councils, committees and unit-based decision-making forums.

Relevance: Active participation in governance structures fosters a culture of inquiry.

Reference: Porter-O’Grady & Malloch (2018)

2. Leadership Responsiveness and Support for Inquiry

Inquiry Follow-Through Score

Measures: Percentage of staff-raised inquiries that lead to documented follow-up actions by leadership.

Relevance: Perceived follow-through from leadership enhances job satisfaction and nurse engagement.

Reference: Laschinger et al. (2014)

Leadership Inquiry Responsiveness Survey

Measures: Feedback on how well leaders respond to staff concerns, including timeliness, transparency and the perceived impact of actions taken.

Relevance: Leader accessibility and responsiveness contribute to workplace empowerment.

Reference: Kanter (1993)

Mentoring and Coaching Index

Measures: Frequency of nurse leaders engaging in coaching or mentoring relationships to foster inquiry and professional development.

Relevance: Structured mentoring improves inquiry-driven leadership.

Reference: Sherman & Cohn (2019)

3. Collaboration and Knowledge Sharing

Interdisciplinary Collaboration Index

Measures: The extent of collaboration across departments, including participation in joint research projects and interdisciplinary team meetings.

Relevance: Interprofessional teamwork enhances inquiry and innovation.

Published by: National Academy of Medicine (2015)

Knowledge Dissemination Metrics

Measures: How often findings from inquiry projects are shared through presentations, posters or publications.

Relevance: Dissemination is a core principle of evidence-based practice.

Reference: Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt (2022)

4. Impact of Inquiry on Nursing Practice and Outcomes

Change Implementation Rate

Measures: Inquiry-driven suggestions that lead to policy, practice or workflow changes.

Relevance: Tracking change adoption is critical for sustainability.

Reference: Proctor et al. (2011)

Impact on Patient Care Metrics

Measures: Whether inquiry-driven changes result in measurable improvements in patient safety, quality of care or operational efficiency.

Relevance: Linking inquiry initiatives to quality metrics demonstrates value.

Reference: Pronovost et al. (2016)

Iowa’s Implementation for Sustainability Framework

Measures: A framework with four phases representing the non-linear nature of implementation within complex health systems where clinicians work and patients receive care.

Relevance: Provides guidance on when to use strategies and how to bundle them by crossing domains to address cognitive, motivational, psychomotor, social and organizational influences.

Contact: UIHCNursingResearchandEBP@uiowa.edu or 319-384-9098

Appendix C: Tools to Monitor Accountability in a Culture of Inquiry

1. Leadership Accountability Index

Purpose: Assesses the degree to which leaders take ownership of decisions, follow through on commitments and are perceived as accountable by their teams.

Components: Measures leadership follow-through, transparency, responsiveness and trust.

Reference: Adapted from the Leadership Accountability Framework.

Connors, R., & Smith, T. (2011). Change the culture, change the game: The breakthrough strategy for energizing your organization and creating accountability for results. Portfolio/Penguin.

2. Organizational Accountability Assessment Tool

Purpose: Evaluates how well an organization fosters a culture of accountability at multiple levels (executive, managerial, front-line staff).

Components: Includes responsibility clarity, follow-up processes, alignment of actions with stated goals and consequences for inaction.

Reference: Developed based on Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Evaluation.

Kirkpatrick, J. D., & Kirkpatrick, W. K. (2016). Kirkpatrick's four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development.

3. Leadership Follow-Through Survey

Purpose: Measures whether leaders act on staff feedback and inquiries. Particularly useful for tracking climate of inquiry implementation.

Components: Includes questions about timeliness, effectiveness, and visibility of leadership action on staff concerns.

Reference: Adapted from the Transformational Leadership Model.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. SAGE Publications.

4. Just Culture Assessment Tool

Purpose: Evaluates whether an organization holds employees accountable in a way that encourages learning rather than punishment.

Components: Measures perceptions of fairness, trust, reporting culture, and leadership accountability.

References: AHRQ,(2017. Just culture assessment tool. Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov

5. Accountability and Engagement Index

Purpose: Assesses how well staff feel leaders are accountable for their decisions and whether inquiry leads to action.

Components: Focuses on communication transparency, decision-making follow-through and employee perception of leadership credibility.

Reference: Developed by the Center for Creative Leadership.

Center for Creative Leadership (2021). The role of accountability in leadership effectiveness. Retrieved from www.ccl.org

6. Leadership Trust and Accountability Scale

Purpose: Measures staff trust in leadership based on how consistently leaders take responsibility for decisions and provide follow-up.

Components: Trust-building behaviors, consistency in decision-making, transparency in actions.

Reference: Based on Covey’s Trust and Accountability Framework.

Covey, S. M. R. (2006). The speed of trust: The one thing that changes everything. Free Press.

7. Scorecard-Based Accountability Measures

Purpose: Tracks leadership performance and organizational accountability related to inquiry efforts.

Components:

- Leadership Scorecards: Tracks leadership performance based on commitment to fostering a climate of inquiry, including follow-up actions and responsiveness.

- CNO/Executive Dashboards: Measures organizational accountability, inquiry resolution rates, and staff satisfaction with leadership actions.

Reference: Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business Press.

11. References

Aitken, S., & Hauger, B. (2025). Doughnut Economics, appreciative inquiry and design Thinking: Designing a desired future. AI Practitioner, 27(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.12781/978-1-907549-62-5-13

American Nurse. (2025, Feb. 13). The symbiotic relationship between nursing and design. https://www.myamericannurse.com/the-symbiotic-relationship-between-nursing-and-design/

Appreciative inquiry – organizing engagement. (n.d.). Organizing Engagement – Advancing Educational Equity. https://organizingengagement.org/models/appreciative-inquiry/

Binder, J. & Watkins, M.D. (2024). To solve a tough problem, Reframe It: Five steps to ensure you don’t jump to solutions. Harvard Business Review, 102(1), 80-89.

Buckwalter, K. C., Cullen, L., Hanrahan, K., Kleiber, C., McCarthy, A. M., Rakel, B., Steelman, V., Tripp‐Reimer, T., & Tucker, S. (2017). Iowa Model of Evidence‐Based Practice: Revisions and Validation. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(3), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12223

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. K. (2005). A Positive Revolution in Change: Appreciative Inquiry. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237404587_A_Positive_Revolution_in_Change_Appreciative_Inquiry

Cooperrider, D.; Whitney, D.D. (2005). Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. In The Change Handbook; Holman, P., Devane, T., Cady, S., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 73–88.

Croft, D. (2024). Guide: RACI Matrix. Learn Lean 6 Sigma. https://www.learnleansigma.com/guides/raci-matrix/ Retrieved on 5/23/25

Dam, R. F., & Siang, T. Y. (2025, March 4). Scamper: How to use the best ideation Methods. The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/learn-how-to-use-the-best-ideation-methods-scamper

Dearholt, S., & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based practice: Models and Guidelines. SIGMA Theta Tau International, Center for Nursing Press.

Design Council. (2025). The Double Diamond - Design Council. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/our-resources/the-double-diamond/ Retrieved 5/21/25

Design kit. (n.d.). https://www.designkit.org/methods.html#filter

Design Thinking Playbook (2025). Mastering the most popular & valuable innovation methods: DT Tools. https://www.dt-toolbook.com/ Retrieved on 5/23/25

Dusin, J., Melanson, A., & Mische-Lawson, L. (2023). Evidence-based practice models and frameworks in the healthcare setting: a scoping review. BMJ Open, 13(5), e071188. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-071188

El-Awady, S. M. M. (2023). Overview of Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA): a patient safety tool. Global Journal on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 6(1), 24–26. https://doi.org/10.36401/jqsh-23-x2

Elsayed, A. M., Zhao, B., Goda, A. E., & Elsetouhi, A. M. (2023). The role of error risk taking and perceived organizational innovation climate in the relationship between perceived psychological safety and innovative work behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1042911

Erickson, J. I., & Pappas, S. (2020). The value of nursing research. JONA the Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(5), 243–244. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000876

George, M., Maxey, J., Rowlands, D., & Upton, M. (2005). The Lean Six Sigma Pocket Toolbook: A Quick Reference Guide to 100 Tools for Improving Process Quality, Speed, and Complexity. McGraw Hill Professional.

Go Lean Six Sigma (GLSS, 2025). 8 Waste Template. https://goleansixsigma.com/8-wastes/?srsltid=AfmBOopqPFsPZLwe2xb1Gq1xGFQBr61s05mn408ECvhK4ljMrpzWPB5d Retrieved on 5/22/25

Houssaini, M. S., Aboutajeddine, A., & Toughrai, I. (2023). Development of a Data-Centric design thinking process for innovative care delivery. HERD Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 17(2), 146–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/19375867231215071

How to improve: Model for improvement: Establishing measures. (n.d.). Institute for Healthcare Improvement. https://www.ihi.org/how-improve-model-improvement-establishing-measures

Innovation Methods. (n.d.). Design Thinking Toolbox. https://www.dt-toolbook.com/

Istvan, B.,Nielsen Jr., P., Eluhu, M., Kozin, B., Winslow, W., Scheinker, D., Patel, K., Favaro, K., Zenios, S., & Schulman, K. (2024). Applying Precedents Thinking to the Intractable Problem of Transaction Costs in Healthcare. Health Management, Policy and Innovation, 9(3). https://hmpi.org/2024/11/19/applying-precedents-thinking-to-the-intractable-problem-of-transaction-costs-in-healthcare/

*Joseph, M. L., Kelly, L., Davis, M., Zimmermann, D., &, Ward, D. (2023). Creating an Organizational Culture and Climate of Meaningful Recognition. Journal of Nursing Administration.

*Joseph, M. L., & Bogue, R. (2018). C-suite roles and competencies to support a culture of shared governance and empowerment. Journal of Nursing Administration, 48, (7-8), 395-399.

Kelley, T., & Kelley, D. (2013). Creative Confidence: Unleashing the creative potential within us all. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB14725647

Kraaijenbrink, J. (2022). The Strategy Handbook: The Secret Sauce To Daily Business Success. Leaders Press.

Lean Enterprise Institute. (2024, February 14). A3 Problem-Solving - A resource Guide | Lean Enterprise Institute. https://www.lean.org/lexicon-terms/a3-report/

The Lean Six Sigma Company (2024). Kanban. https://www.theleansixsigmacompany.us/kanban/ Retrieved on 5/23/25

Lewrick, M. (2018). The Design Thinking Playbook: Mindful Digital transformation of teams, products, services, businesses and ecosystems. http://scholarvox.library.inseec-u.com/catalog/book/88873523

Lewrick, M., Link, P., & Leifer, L. (2020). The Design Thinking Toolbox: A Guide to Mastering the Most Popular and Valuable Innovation Methods. John Wiley & Sons.

Majers, J. S., & Warshawsky, N. (2020). Evidence-Based Decision-Making for nurse leaders. Nurse Leader, 18(5), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.06.006

Melnyk, B. M. (2012). Achieving a High-Reliability Organization through implementation of the ARCC Model for Systemwide Sustainability of Evidence-Based Practice. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 36(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/naq.0b013e318249fb6a

Nelson, R. (2020). Nursing innovation. AJN American Journal of Nursing, 120(3), 18–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.naj.0000656300.77328.fe

Nurse Manager Interviews. (2024/2025). [Unpublished raw data on nurse manager perspectives on inquiry culture].

Schiff, G. D., & Rucker, T. D. (2001). Beyond Structure-Process-Outcome: Donabedian’s Seven Pillars and Eleven Buttresses of Quality. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 27(3), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27015-1

Sennequier, P. (2025). Amplifying the strengths of our systems: the effectiveness of appreciative approaches to change management. AI Practitioner, 27(1), 61–65. ISBN 978-1-907549-62-5

Six Domains of Healthcare Quality (n.d.). Content last reviewed December 2022. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

Tahan, H. M., Rivera, R. R., Carter, E. J., Gallagher, K. A., Fitzpatrick, J. J., & Manzano, W. M. (2016). Evidence-Based Nursing Practice: the PEACE Framework. Nurse Leader, 14(1), 57–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2015.07.012

Thacker, R. (2022, June 3). Culture of inquiry. Nurses. https://uamshealth.com/nurses/newsletters/culture-of-inquiry/

Utley, J., & Klebahn, P. (2022). IdeaFlow: The Only Business Metric That Matters. Penguin.

Van Graas, R., & Gobbens, R. J. (2023). Learning and developing together for improving the quality of care in a nursing home, Is appreciative inquiry the key? Healthcare, 11(13), 1840. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11131840

Voyce, J., Gouveia, M. J. B., Medinas, M. A., Santos, A. S., & Ferreira, R. F. (2015). A Donabedian model of the quality of nursing care from nurses’ perspectives in a Portuguese hospital: a pilot study. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 23(3), 474–484. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.23.3.474

Watkins, M. D. (2024). The Six Disciplines of Strategic Thinking: Leading Your Organization Into the Future. Harper Business.

Wymer, J. A., Weberg, D. R., Stucky, C. H., & Allbaugh, N. N. (2023). Human-Centered Design: principles for successful leadership across health care teams and technology. Nurse Leader, 21(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2022.11.004

Zenios, S., & Favaro, K. (2025). Precedents Thinking: How to innovate by combining old ideas. Harvard Business Review, 103(2), 55-63.

American Organization for Nursing Leadership. AONL Workforce Compendium. Chicago, IL: American Organization for Nursing Leadership; 2023. AONL_WorkforceCompendium.pdf

Edgoose, J., Quiogue, M., & Sidhar, K. (2019). How to identify, understand and unlearn implicit bias in patient care. https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2019/0700/p29.html

Gray, M., Umoren, R., Sayre, C., Hagan, A., Jackson, K., Wong, K., & Kim, S. (2024). Finding your voice: a large-scale nursing training in speaking up and listening skills. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 55(6), 309-316. doi:10.3928/00220124-20240201-05

Luther, B., & Flattes, V. (2022). Bias and the psychological safety in healthcare teams. Orthopaedic Nursing, 41(2), 118-122. DOI: 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000831

Gee, P., Olsen, G., Kranz, C., Roberts, J., Sakata, T., Srivastava, R. (2022). Creating a shared culture of inquiry. Quality Management in Healthcare Journal, 31:3, 151-153.

Gong, L., Liu, Z., Rong, Y., Fu, L. (2021). Inclusive leadership, ambidextrous innovation and organizational performance: the moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Leadership & Organizational Development Jornal, 42:5, 783-801.

Laschinger, H., Havens, D. (1996). Staff Nurse Work Empowerment and Perceived Control over Nursing Practice: Conditions for Work Effectiveness. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 26(9): 27-35.

Lee, SE, Seo, JK (2024). Effects of nurse managers’ inclusive leadership on nurses’ psychological safety and innovative work behavior: The moderating role of collectivism. Sigma Theta Tau International Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 56: 554-562

Spreitzer, G. (2017). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (5), https://doi.org/10.5465/256865

Taplin, S. (2024). Relationships: Unlocking success through meaningful relationships. Forbes. Retrieved on 12/31/24 at Unlocking Success Through Meaningful Connections And Relationships

van Dyk EC, van Rensburg GH, van Rensburg ESJ (2021). A model to foster and facilitate trust and trusting relationships in the nursing education context. Journal of Interdisciplinary Health Sciences, 3;26:1645. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v26i0.1645. PMID: 34956655; PMCID: PMC8678963.

Clark, T. R. (2020). The 4 stages of psychological safety: Defining the path to inclusion and innovation. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Gross, B., Rusin, L., Kiesewetter, J., Zottmann, J., Fischer, M., Pruckner, S., & Zech, A. (2019). Crew resource management training: a systematic review of intervention, design, training conditions, and evaluation. BMJ Open, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025247

Joseph, M. L., Kelly, L., Davis, M., Zimmermann, D., &, Ward, D. (2023). Creating an Organizational Culture and Climate of Meaningful Recognition. Journal of Nursing Administration.

Norman, M. & Helbig, K. The Psychological Safety Playbook: Lead More Powerfully by Being More Human• Karolin Helbig © 2023

Edmondson, A. C., & Bransby, D. P. (2023). Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 55-78.

Ito, A., Sato, K., Yumoto, Y., Sasaki, M., & Ogata, Y. (2022). A concept analysis of psychological safety: Further understanding for application to health care. Nursing Open, 9(1), 467-489.

Akkoç, İ., Türe, A., Arun, K., & Okun, O. (2022). Mediator effects of psychological empowerment between ethical climate and innovative culture on performance and innovation in nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(7), 2324-2334.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2017). Just Culture Assessment Tool. Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). (2020). Root Cause Analysis Toolkit. Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking creates new alternatives for business and society. Harper Business.

Cooperrider, D. L., & Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change. Berrett-Koehler.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350-383.

Gerard, S. O., Kazer, M. W., & Babington, L. (2014). Shared governance: Nurses' and managers' perceptions of empowerment. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(2), 115-120.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). (2021). Leadership for Learning Health Systems. Retrieved from www.ihi.org

Kanter, R. M. (1993). Men and women of the corporation. Basic Books.

Laschinger, H. K., Wong, C. A., Cummings, G. G., & Grau, A. L. (2014). Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: The value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nursing Economics, 32(1), 5-15.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2022). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Wolters Kluwer.

National Academy of Medicine. (2015). Measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. The National Academies Press.

Porter-O’Grady, T., & Malloch, K. (2018). Quantum leadership: Creating sustainable value in health care. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Pronovost, P. J., Cleeman, J. I., Wright, D., & Srinivasan, A. (2016). Fifteen years after To Err Is Human: A success story to learn from. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(6), 396-404.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., ... & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65-76.

Sherman, R. O., & Cohn, T. M. (2019). The impact of mentoring on nurse leadership. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 43(3), 192-198.g