Strengthening Nurse Leadership | Compendium 2.0

1. Process Overview

Best practice examples were reviewed from the first compendium that informed the development of Compendium 2.0. These practices were ranked based on current leadership priorities to determine which to explore further.

Several key themes emerged and were connected to the AONL leadership competency framework, with the "leader within" concept serving as the foundation for all competencies. The "leader within" represents the self-awareness, personal values and individual leadership style that each nurse must develop before leading others.

Themes alignment with AONL competencies

| AONL Leadership Competency | Themes | Goal | Intervention/Strategy |

Communication & Relationship Management

| Career Frameworks, People and Programs | Bridge clinical-to-management gap and provide clear advancement paths. Reduce administrative burden and enhance well-being. | Seek out executive commitment. Institute succession planning, career mapping, transition-to-practice (TTP) programs, career ladders and a competency-based leadership development program. Launch nurse leader governance councils. Conduct a value stream analysis. |

| Knowledge of the Care Environment | Digital Technology | Equip nurse leaders with resources to lead digital technology and quality initiatives | Utilize AONL guiding principles for digital technology. Conduct self-assessment by evaluating own understanding of digital technology. |

| Business Skills and Principles | Span of Accountability Budgets/Finance Intelligence/FTEs and Staffing | Make determinations to adjust relative to span of accountability. Provide best practice resources for emerging leaders. | Use span of accountability tools and references. Support pursuing advanced degrees and educational programs aligned with business skills. Engage in mutual learning with finance partners. Partner with academic institutions to hardwire finance and budgeting as core competencies. |

| Leadership | Leadership competencies and leading virtual teams, workforce leadership. | Provide relational connection between remote and onsite teams. | Implement virtual leader rounding, connection-building activities. Embrace the AONL core competencies of communication and relationship building. |

2. Themes from Compendium 1.0 Best Practice Examples

Structural support and protected time for leaders at all levels (emerging, experienced and executive) are foundational to supporting and advancing nurse leaders.

The following programs reduced administrative burdens, introduced structure around skills development and created targeted assessment tools to measurably improve nurse leader satisfaction and efficacy:

- One organization reduced nurse leader burden by applying lean methodology to eliminate low-value tasks, allowing leaders to focus on coaching their teams.

- Another organization helped clinical experts improve their leadership abilities through structured monthly development sessions that progressed from basic skills to strategic thinking.

- An academic medical center’s think tank created a survey that strengthened nurse leadership development by measuring and supporting professional identity growth.

Read more about these programs below:

A. Best practice example: leadership training connects teams

Health care organizations need structured ways to develop clinical experts into successful leaders. In 2021, a large academic health system launched the Hierarchy, Accountability, and Responsibility Program (HARP) to map clear advancement paths for nurses to move into leadership positions.

Under HARP and drawing from Maslow's needs hierarchy and AONL leadership skills, participants start with basic management needs and build up to strategic thinking. Front-line nurse leaders hold monthly sessions, while a new component supports first-year managers.

Current data demonstrates success: nurse turnover stays below 10%, and managers report less burnout, which program leaders track through regular surveys. HARP has also strengthened interprofessional connections. Managers who once rarely talked to colleagues in nearby buildings now regularly connect and support each other.

The program succeeds through executive commitment and evidence-based teaching methods. Each session includes group work, wellness activities and practical leadership lessons. Nurse leaders nationwide have taken notice, and many are seeking to replicate this model.

B. Best practice example: nursing excellence tool bridges clinical-to-management gap

In 2021, a large academic health system launched the Excellence in Ambulatory Leadership Evaluation (EAGLE) Project to map clear advancement paths for nurses moving into leadership positions. The project provides a structured framework for ambulatory care leadership development.

The program connects job descriptions, competencies and daily responsibilities to digital portfolios. The program succeeds through intentional design. Leaders start by identifying three to five key skills they want to work on. Then, they document their progress through simple evaluation forms in Microsoft Teams during their mid-year and annual reviews. Most importantly, program leaders commit to ongoing listening — gathering input from all 200 leaders, not just committees, to understand what skills matter most and what brings joy to their practice. This process shapes yearly updates to keep competencies current.

Since launching, EAGLE has evolved significantly. Its leaders refined requirements based on feedback, securing protected time through formal agreements and improving digital access. What began as a nursing tool now guides development across clinical and administrative roles. When the organization's virtual care platform expanded from 50 to 160 staff members, EAGLE helped the organization triple its leadership positions from three managers to 12.

Other health systems can replicate this success by defining clear competencies, creating practical evaluation tools and listening to leaders' needs.

For more information:

Appendix B: Coaching Worksheet Template: Nurse Manager

Appendix C: Nurse Manager - Intermediate Competency Grid

C. Best practice example: professional identity in nursing survey strengthens career development

The Professional Identity in Nursing Survey (PINS) initiative emerged from a collaborative scholarship beginning in 2018 at a University of Kansas think tank. There, 50 nurse leaders gathered to define professional nursing identity and identify its core constructs. This framework, which measures and supports professional identity development, has since gained widespread adoption in nursing education and practice.

The framework consists of a 30-item self-assessment where nurses rate their proficiency across professional identity domains: values and ethics, knowledge, nurse as leader and professional comportment. Nurses also evaluate how well their workplace supports these professional identity domains.

Scholars tested this framework among 1,700 nursing professionals — first with educators and administrators across U.S. nursing schools, then with practicing nurses in clinical settings. A survey showed 92% of nurses reported that colleagues with strong professional identity had higher impact in their roles. The assessment consistently identifies areas where nurses need development and where workplace changes could strengthen professional practice.

Two large U.S. health systems are currently piloting four-to-six-week microlearning programs based on the PINS framework, measuring impact on unit-specific quality metrics and nurse performance indicators. Initial data shows improvements in how nurses view their own professional capabilities and their work environment. The framework's effectiveness led all three national nursing education accrediting bodies to require professional identity development in their standards. The framework has been adopted internationally, with nursing programs in the United Kingdom and Africa implementing PINS-based curricula. An international society formed to advance the work globally.

While specific return on investment data is still being gathered through pilot programs, the growing evidence of PINS impact on nurse performance has led one major U.S. health system to adopt professional identity formation as a cornerstone of its strategy to address burnout and retention challenges.

Organizations implementing the PIN framework should take specific steps:

- Assign an executive leader to oversee the program.

- Build the framework into existing nurse training at both hospitals and nursing schools.

- Regularly measure progress using the assessment tool and provide ongoing education as nurses advance in their careers.

Success under this framework requires both nursing schools and hospitals to reinforce professional identity development at every stage.

3. Assessment of Best Practices, Action Steps and Evaluation Methods

A. Career frameworks, people and programs

Nurse leader turnover presents significant challenges for organizations, with vacancies affecting patient care, staff morale, financial performance and daily operations. The 2025 AONL Foundation Insights study of 2,992 nurse leaders revealed that 23% indicated intent to leave and another 23% reported they might leave. Of those intending to depart, 35% were unsure of their timeline, 21% planned to leave within two years, and the remaining 44% within one year.

We recommend the following best practices to help retain leaders.

1. Bridge management gaps and provide clear advancement paths

Research shows that structured succession planning prevents leadership gaps (Ghidini et al., 2024). Successful programs combine systematic leadership assessment across all levels, partnerships with HR teams to identify high-potential staff and targeted development opportunities.

Once identified, these emerging leaders need developmental support. Organizations should integrate leadership development programs and mentorship residencies to cultivate high-potential and emerging leaders (Bernard, 2014; Bognar et al., 2021; Brigstock et al., 2023). This preparation allows future leaders to develop skills and confidence before assuming leadership positions, ensuring smoother transitions while reducing replacement costs.

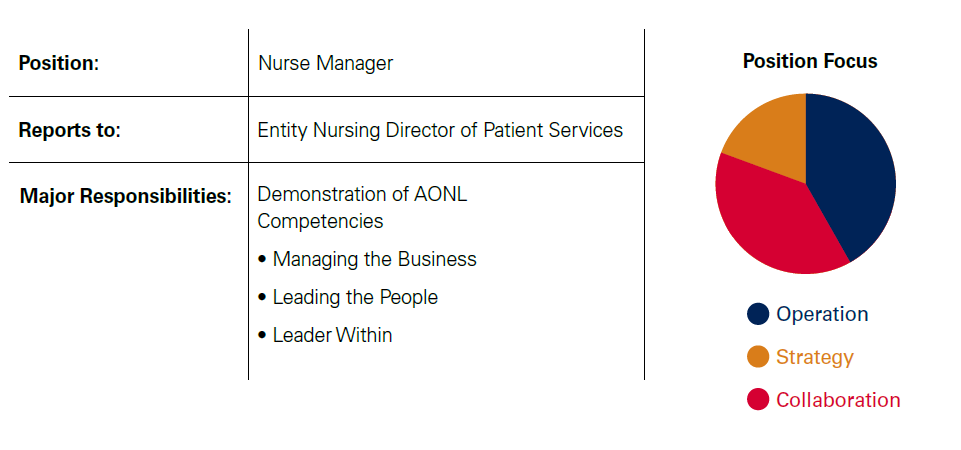

Success maps help leaders identify the competencies required for advancement and prepare for the next role before promotion. Success maps, which are customized documents, outline the key elements for a nursing role that positions a nurse leader for success, as well as growth and development. Appendix A: Example Success Map.

They may include descriptions of the following:

- The role

- To whom who the person in that role reports

- Major responsibilities

- Educational and licensure requirements

- Essential experiences required for the role

- Future trends of the role

- Key relationships

- Important groups to participate in

- Specific leader competencies from the AONL competency model

In some cases, organizations appoint interim nurse leaders when permanent placements are delayed. Organizations can support them with structured onboarding, mentorship and targeted training. AONL’s e-manual for interim nurse managers provides a framework for role transition and professional development (Parchment et al., 2023).

Recommendations and action steps:

- Leaders need dedicated time to assess leadership bench strength across all levels, from charge nurses to chief nursing officers (CNOs).

- Make succession planning a core leadership competency to build a culture of continuous development. Identify succession planning as an integral part of the nursing strategic plan and job descriptions of all leaders (Chan, 2022; Desarno et al, 2021).

- Administrators should use the 2023/2024 AONL Workforce Committee’s succession planning guide to develop or improve their leadership transition framework.

- Success maps should outline key competencies, major responsibilities, educational requirements and future trends for roles including:

- CNO, Vice President, Director, Nurse Manager, Assistant Nurse Manager and Charge Nurse

- These maps align with the AONL competency model to provide clear development paths.

Measuring the success of succession plans

Organizations can measure succession planning by how quickly they fill leadership roles with prepared internal candidates. When teams are able to fill senior positions within four weeks of a planned departure — without relying on external recruitment — that reflects a healthy leadership pipeline (Suby, 2025). Another key indicator is the percentage of leadership roles filled through internal promotion, which reflects how well the organization is developing and advancing its talent (Krivanek et al., 2023; Titzer et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2014).

The competencies of the individuals stepping into these roles also matter. New leaders should demonstrate readiness through strong performance in key areas, including employee satisfaction, team stability, financial management and turnover levels. Organizations can track these indicators using standard new-leader performance metrics.

Senior leaders should also assess whether successors have mastered essential business skills. These include managing full-time equivalent (FTE) budgets and staffing plans, interpreting productivity reports by skill mix, and correcting payroll or scheduling issues within one or two pay periods (Waxman & Knighten, 2023). Leaders who consistently apply these skills contribute to stronger operational results and more stable teams.

Additional metrics include:

- Leadership turnover rate. Target an annual turnover rate below 10%. While average turnover rates vary, recent data show that managers exit their roles at an average rate of 8.15% when accounting for all tenure ranges and reasons for departure (American Organization for Nursing Leadership & Laudio Insights, 2024).

- Internal fill rate. Measure the percentage of leadership positions filled by internal candidates. A suggested target is 60% or greater.

- Time-to-fill leadership roles. Track the number of days between vacancy announcement and role appointment. A benchmark of fewer than 60 days is commonly used.

- Pipeline readiness. Evaluate the proportion of departments with documented succession plans and active participation in development programs. Recommended targets include 100% of departments with succession plans and at least 85% of identified successors participating in development activities.

- Competency attainment. Conduct structured self-assessments aligned with success profiles or leadership maps, with a goal of at least 90% of successors rated as “ready now” or “ready soon.”

- New leader performance. Assess key outcomes such as employee engagement, staff turnover, satisfaction scores and financial performance to determine how well new leaders are transitioning into their roles.

2. Support leaders in transition-to-practice programs

Many nurse leaders enter leadership roles without formal preparation, making the transition challenging. The increasing complexity of their roles often delays competency development, leaving new leaders struggling to navigate their responsibilities. While nurses value experiential learning, relying on trial and error is inefficient. Structured transition-to-practice (TTP) and residency programs provide a more effective and intentional approach to leadership development (Warshawsky et al., 2020).

Unlike generalized orientation or leadership courses, TTP and residency programs provide targeted support for new leaders. These programs help nurse managers and other leadership roles gain essential competencies, adapt to organizational expectations, and build confidence in decision-making. While some organizations offer pieces of leadership transition programs, many lack a coordinated, comprehensive structure (Grubaugh et al., 2023; Ghidini et al., 2024).

Leadership TTP programs also benefit experienced leaders transitioning to a new organization. Even those with prior leadership experience need support in understanding new processes, cultural expectations and system-specific leadership challenges.

Organizations can develop internal TTP programs using AONL’s competency frameworks or adopt external models (Ramseur et al., 2018; Ficara et al., 2021; Ghidini et al., 2024). The American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC) Magnet Recognition Program has required TTP programs for all levels since 2019 (Lawson, 2020). Organizations can choose from existing programs, build their own or integrate both approaches to create a structured, scalable model. To assess effectiveness, they can apply NSI principles by tracking nurse leader turnover rates and associated costs.

Recommendations and action steps:

For a TTP or residency program to be successful, organizations should incorporate:

- Mentorship and peer support. Pairing new leaders with experienced mentors fosters learning, confidence and role adaptation.

- Flexible program structures. Organizations with smaller leadership cohorts may benefit from shared programs at a system-wide or state level.

- Organizational support. Involving human resources, leadership development teams and academic-practice partnerships strengthens program effectiveness.

- Structured learning components. Programs should define leadership expectations, organizational culture and required competencies.

Measuring the success of leadership transition programs

To evaluate effectiveness, organizations should track:

- Competency development and leadership readiness.

- Job satisfaction and retention rates.

- Confidence and sense of belonging in leadership roles.

- Engagement and professional growth opportunities.

Some organizations use structured check-ins, self-assessments or dashboards developed in partnership with internal analytics teams or external vendors to track progress over time. Sharing real-time data with senior leaders and mentors can help identify early successes or gaps in leadership transition efforts.

Available External Programs and Resources

AONL provides established frameworks for leadership development, including:

- Nurse Manager Transition to Practice (on-demand and facilitated options).

- Nurse Leader Core Competencies.

- Functional competencies for nurse executive and nurse manager roles.

3. Retain leaders and provide advanced development programs

Career ladders for bedside nurses were first introduced in the 1970s to recognize expertise, experience and clinical skills. These programs allowed nurses to advance professionally without moving into management roles, leading to improved retention, job satisfaction and clinical competency.

However, career ladders for nurse managers and leaders remain rare. Establishing leadership career ladders can help retain top leadership talent and support succession planning. Research by Warshawsky & Cramer (2019) found that nurse managers take more than seven years to become proficient, and struggle the most with finance, strategic management and performance improvement. Structured programs such as career ladders and leadership development initiatives can accelerate competency growth and make leadership development more efficient and rewarding.

Recommendations and action steps:

- Administrators should design professional development programs to support leaders at all levels.

- They should design the programs to accommodate emerging competencies such as those related to technology and integration.

- Conducting annual educational needs assessments or engaging leaders in direct conversations about their development goals can inform effective strategies for career growth (Grubaugh et al., 2023).

- Mentorship as part of career ladders can further support, challenge and inspire leadership development.

- Utilize established frameworks when developing career advancement pathways to ensure consistency and clarity.

- Gather feedback from potential participants to ensure career ladders are achievable, valuable and meaningful to health care professionals.

- Implement program evaluation methods to measure effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Build flexibility into development programs to ensure they can adapt to the emerging professional requirements.

Measuring the success of career ladders:

- Organizations can measure program success by tracking participation rates, internal promotion metrics, job satisfaction scores, retention rates, leadership confidence levels, engagement scores and improved staff and patient outcomes.

- Program designers should build evaluation mechanisms, such as regular educational needs assessments, into the structure to guide ongoing improvements.

- Organizations should start with established frameworks and then gather participant feedback on achievability, value and meaningfulness.

If an internal career ladder or professional development opportunities are not available, there are various external opportunities, such as:

- AONL fellowships for nurse managers, directors and executives

- Opportunities through the Nurse Manager Institute.

- Leadership development for nurse managers through the Leadership Lab.

- Administrative Supervisor Program.

- Coldiron Senior Nurse Fellowship Program.

B. Reducing nurse manager workload to strengthen retention

Nurse managers find their greatest satisfaction in directly supporting their teams. However, organizations often overwhelm managers with hospital-wide responsibilities that pull them from these core functions. Organizations must balance unit-level and organizational demands to create sustainable workloads. Managers need protected time to coach their teams toward quality outcomes, while organizations should eliminate tasks that don't directly support unit or organizational goals (AONL Foundation, 2022; Hahn et al., 2021). We recommend the following best practices to help reduce workload burden:

1. Utilize nurse leader governance councils for better communication, culture

Nurse leader councils create dedicated spaces for managers to share best practices and develop collective knowledge. These forums allow managers to prioritize initiatives and distribute project responsibilities across the leadership team. At one organization, a group of nurse leaders started a council to give front-line leaders more voice and support. After joining, they reported feeling more empowered and confident. They were hopeful the council would lead to a stronger, more supportive culture over time. (Keith et al., 2021; Stagg et al., 2023; Warshawsky et al., 2016).

These councils also build important connections between day-shift managers and off-shift supervisors. Managers often instruct staff to contact them after hours for issues that supervisors could address. By bringing these leadership groups together regularly, organizations build trust through social connections. These collaborative structures help managers decompress, strengthen resilience and increase engagement (Weaver et al., 2021).

2. Conduct a value stream analysis of nurse managers’ work

Organizations often view nurse managers as the primary channel for communicating with front-line staff. This perspective leads to continually adding responsibilities without removing existing ones, creating unsustainable workloads over time.

Forward-thinking organizations conduct systematic workload analyses with their managers. This process involves managers documenting all current tasks and responsibilities, then evaluating each for its true value. Teams decide whether each task should remain a priority, be transferred to another department or be eliminated entirely. This structured approach creates manageable workloads that focus managers' time on high-impact activities (AONL Foundation, 2022).

3. Provide structured leadership development programs

Research from multiple studies shows competency-based leadership development produces measurable improvements in leadership readiness, retention, professional integration and organizational outcomes (Harper & Maloney, 2022; McGarity et al., 2020; Titzer et al., 2014; Välimäki et al., 2023; Yudianto et al., 2023). Effective programs incorporate standardized competencies, mentorship, experiential learning, networking opportunities, self-reflection and succession planning.

While nurse managers understand evidence-based clinical practice, they often rely on experience and intuition for leadership decisions. Structured development programs like manager residencies and leadership academies bridge this gap by combining live instruction with flexible online learning. These programs build operational leadership skills while reinforcing core competencies. Regular assessments provide real-time feedback that helps refine program content to support role clarity, enhance decision-making and strengthen leadership pipelines — creating stability in nursing leadership.

C. Digital transformation for nurse leaders: framework for action

Nurse leaders are essential bridges between clinical practice and technology. The following best practices help incorporate technology into nurse leader programs.

1. Embrace digital competency learning programs

AONL's framework for digital leadership establishes nurse leaders as key drivers of technology adoption.

The guiding principles emphasize building digital competency at all levels, promoting cross-team collaboration and ensuring end-user involvement in technology decisions. The framework also recommends that nurse leaders align digital initiatives with organizational goals, encourage innovation and use data to improve outcomes.

These additional tools can help nurse leaders build digital competency:

- The Digital Skills Assessment Tool (DSAT) identifies specific literacy gaps, which helps leaders develop targeted technology training.

- The Nursing Digital Application Skill Scale (NDASS) helps organizations design customized skill development resources based on assessment results (Qin et al., 2024). Learn more about the scale.

Recommendations and action steps for building digital competency:

- Nurse leaders should collaborate actively with IT, digital analytics and informatics teams to drive technology initiatives. Organizations must establish nurse-led governance structures for technology approval and strategy development.

- Nursing departments should incorporate digital transformation goals into their strategic plans. During onboarding, new nurse leaders should complete digital competency assessments to identify learning needs and establish measurement baselines.

- Organizations should add digital competency requirements to nurse manager, director and executive role descriptions. Leaders must ensure proper technology orientation and ongoing training for all nursing staff while encouraging open discussion about adoption barriers.

- Nurse leaders should champion data-driven decision making using analytics tools and visualizations. Organizations must update policies to address data privacy and cybersecurity concerns.

How to evaluate digital competency programs:

Organizations can measure success through multiple indicators: increased adoption rates of digital tools, reduced documentation errors, improved patient satisfaction with digital access, training completion percentages and nurse leaders' confidence with technology. For example, nurse leaders and clinical teams at a rural health system in the Midwest partnered with IT to implement a standardized Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol embedded in the electronic medical record (EMR). The pilot reduced the average length of stay for colon resections by 2.7 days without increasing readmissions, and patient satisfaction improved. Close collaboration between IT and clinical operations led to consistent electronic health record (EHR) workflows, supported safe and compliant documentation, and enabled systemwide expansion across all surgical specialties (T. J. Larsen-Engelkes, 2025).

In another example, a Pennsylvania-based health system struggled with inconsistent nursing documentation practices and workflow inefficiencies after implementing a new EMR. Recognizing that nurse leaders needed training to better evaluate EMR tools and lead improvements, the health system launched an informatics training program, which prepared nurse leaders to use advanced EMR functions, data analytics and design better workflows. The program also embedded informatics leaders within units to lead documentation improvement efforts. Because nurse leaders could better use the EMR's documentation templates and flowsheets their documentation time dropped by 30% in med-surge units. Clinical compliance improved, resulting in a 15% increase in sepsis bundle adherence. With better workflows, nurses reduced alarm fatigue and were otherwise more engaged, with higher Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems scores (related to nursing communication and responsiveness) to show for it (Sensmeier, Anderson, & Shaw, 2019; American Nursing Informatics Association, n.d.; Geisinger, 2018—2021).

Additional metrics include increased use of real-time analytics for clinical decisions and reduced security breaches.

D. Reassessing nurse leaders’ spans of accountability

Nurse leaders today manage more responsibilities than even just five years ago. The number of staff a nurse leader supervises — their span of accountability — directly determines how effective they can be and how well patients fare under their leadership. We recommend the following best practices.

1. Create balanced span of accountability

Reducing nurse managers' spans of control would improve both patient safety and nurse retention. Nursing leadership today spans a broad range of administrative and clinical responsibilities, and modern span of control now accounts for direct reports, team experience, work complexity, supervision needs and technology use (Ruffin et al., 2023).

Recent workforce and safety data underscore the urgency of this issue. While hospital-wide staffing increased 13%-17% per bed and RN staffing increased 20-23%, nursing department staffing per bed has decreased by 0.99-2.8%. Simultaneously, patient acuity rose 6% since pre-pandemic levels. This shift leaves fewer permanent staff care for sicker patients, any many hospitals increasingly rely on contract labor — which increases falls and medication errors when exceeding 15% of total hours (Suby, 2025).

This strain shows in a growing number of patient safety incidents, which rose 19% from 2021-2022, with falls representing 42% of incidents. Total sentinel events jumped from 910 in 2019 to 1,441 in 2022 (Suby, 2025). This coincides with decreasing support hours, pulling nurses from bedside care to non-nursing tasks.

Meanwhile, the composition of the hospital workforce is shifting. Nursing staff now make up only 29% of hospital employees (down from 40-49% pre-2019). Nurse managers typically oversee 50-100 staff members, contributing to high turnover from burnout (Cummings et al., 2020; AONL, 2022). As full-time staff ratios approach the critical 50% threshold, nurse managers face increasingly unstable scheduling and staffing gaps, with reduced time for mentoring. Declining education hours further undermine staff development and retention (Suby, 2025).

Recommended actions for balancing nurse leader workloads:

To improve nurse leaders' span of accountability, organizations should invest in assistant managers, clinical coordinators or permanent charge nurses who can help managers support staff development. Leaders can use resources from the AONL Workforce Committee 2024 Span of Control Subcommittee Report, including the Span of Control Assessment Tool (pages 5-6 of the report) and the ROI Calculator (pages 7-8), to evaluate whether current spans of control are appropriate and to estimate the financial impact of realigning support roles.

How to measure efforts to reduce span of accountability:

Organizations should calculate nurse leaders’ span of control using actual headcount, not full-time employees (FTEs), to reflect true workload. This approach supports more accurate staffing, reduces scheduling conflicts, controls costs and improves retention. Leaders can use the AONL Span of Control Assessment Tool (pages 5-6) to evaluate role complexity and determine whether adjustments are needed.

The AONL and Laudio Quantifying Nurse Manager Impact report (Spring 2024) found that wider spans of control were associated with higher nurse leader turnover and increased overtime. The report also found that nurse managers who have at least one meaningful interaction per team member per month saw a 7 percentage point increase in RN retention annually. Reducing span of control gives managers more time for those meaningful connections, leading to improved retention, engagement and financial outcomes.

E. How nurse leaders can sharpen their budget and finance acumen

Nurse leaders must manage financial resources using principles of economics, finance, accounting and budgeting (AONL, 2022). Many nurse leaders report that finance and budgeting are the most challenging aspects of their role.

We recommend the following best practices:

1. Pursue advanced education in business and finance

Research shows that nurse leaders often lack financial knowledge. Studies comparing different learning approaches found that advanced degrees like MSN or MBA programs provide the most effective financial education for nurse leaders (Brydges et al., 2019). Another study identified graduate-level business education as the strongest predictor of self-perceived financial competence among nurse leaders (Welch, 2022).

2. Create dedicated finance-nursing liaison positions

Nurse leaders drive better organizational performance when they have direct access to financial expertise. Interdepartmental collaboration between nursing and finance departments improves organizational financial performance (McFarlan, 2020). Organizations should implement multidisciplinary training programs that equip nurse leaders with essential fiscal management knowledge and skills.

For example, a Rhode Island health care organization created a successful model by partnering nursing and accounting departments to strengthen nurse leaders' business acumen. The program trained leaders in data interpretation, cost-effective practices and fiscal stewardship to promote leadership accountability. This collaboration delivered measurable results: the organization achieved a 21% reduction in incremental overtime, a 7% reduction in contract labor within four months and ran inpatient units 5% under budget for medical/surgical supplies through focused supply variance reporting (Danner & Weiss, 2024).

3. Establish finance as a core leadership competency

Nursing departments consume a large portion of hospital budgets and directly impact financial stability. Nurse leaders must create efficient, safe care environments, which requires financial knowledge (Bayram et al., 2022). Despite this need, finance often remains outside core leadership training. Organizations should establish financial competency as a fundamental leadership requirement with ongoing education opportunities.

Nurse leaders particularly struggle with converting FTE budgets into practical staffing plans. This process includes translating budgeted FTEs into hours and shifts, calculating full-time and part-time position requirements, determining weekend coverage needs and creating fair schedules that meet labor standards. While nurse leaders often understand general principles, they need more support with these specific calculations and their relationships to position control and daily staffing (Waxman & Knighten, 2023).

The AONL Finance and Business Skills for Nurse Managers course provides additional education and tools to help leaders apply these concepts in practice.

Recommendations and action steps:

Schools of nursing and health care organizations should collaborate to integrate finance and business content into undergraduate curricula. This foundational knowledge helps prepare new nurses to understand how their decisions affect organizational performance (Bayram et al., 2022).

For nurses and leaders already in practice, organizations should offer or promote access to continuing education in financial management. Recommended programs include:

- AONL Finance and Business Skills for Nurse Managers.

- AONL Healthcare Finance for Nurse Executives (virtual).

- Finance 101 for Health Care Professionals on Nurse.com.

These programs build financial acumen through Nursing Continuing Professional Development credits or certificates and support stronger leadership at all levels.

How to measure improvements in business acumen:

Based on leadership instruction and applied teaching, organizations can assess improvements in nurse leaders’ business acumen by tracking how effectively they manage financial and staffing responsibilities in real time. (Suby, 2023)

The following observed indicators are adapted from “Operational excellence & effective staffing strategies ” (Suby, 2023):

- Application of FTE budgets, position control, work agreements (full-time, part-time, per diem/as-needed) and daily staffing adjustments to actual and budgeted hours and dollars per workload unit of service.

- Use of two-pay-period strategies to address payroll and scheduling leakage.

- Attainment of practical benchmarks such as:

- Overtime and premium pay below 45% of total worked hours per pay period.

- Turnover (with and without unit erosion) below 10% of total worked hours per pay period.

- Unplanned absences below 5% of total worked hours per pay period.

- Paid absences below 10% of total worked hours per pay period.

- Improved ability to communicate proposed strategies to assistant nurse managers, charge nurses, float pool leaders and unit staff to build alignment and support unit goals.

These benchmarks reflect experiential knowledge shared in leadership education and may vary by organization.

F. Leadership competencies and leading virtual teams

Nurse leaders today need specific competencies to manage departments, budgets, staff, and patient care delivery. As hospitals adopt telehealth, virtual nursing and other new approaches to care, leadership practices must evolve to meet these changes.

We recommend the following best practices:

1. Develop virtual team engagement strategies

Virtual nursing now plays a role in many care models, supporting medication reconciliation, documentation, novice nurse guidance and patient education (Clipper, 2024). Leaders can build engagement with virtual teams through:

- Customized onboarding processes based the organization’s virtual care structure.

- Virtual leadership rounds.

- Connection-building activities.

- Regular communication and feedback (Scortzaru et al., 2024).

Relational leadership that creates connection opportunities and provides technology support helps maintain nursing's human-centered focus. Research shows that consistent, purposeful interactions from nurse leaders directly improve nurse retention (Darling, 2024; Zangerle & Martin, 2024).

2. Build digital technology competency

Nurse leaders must understand evolving technologies and artificial intelligence applications. Successful digital transformation requires collaboration across both in-person and remote teams. Leaders should understand specific problems needing solutions and involve key stakeholders in technology selection (Morin et al., 2024).

Despite rapid technological advancement, human-centered relational leadership remains fundamental (Hougaard & Carter, 2024). Leaders should:

- Assess their own digital knowledge gaps using a structured competency assessment tool.

- Align technology initiatives with organizational goals.

- Create innovation-friendly environments.

- Use data to drive decisions.

3. Master hybrid team leadership

Many nurse leaders now manage hybrid teams with both remote and in-person staff. This model appears in many settings, such as when bedside nurses work with virtual nurses providing remote surveillance. Successful hybrid team leadership requires skills in building inclusivity, collaboration, communication, trust and psychological safety (Hincapie & Costa, 2024).

Recommendations and action steps for improving hybrid team leadership:

Connecting remote and in-person staff helps build relationships that improve communication. These relationships directly affect patient safety and staff well-being (Oleksa-Marewska & Tokar, 2022; Rouleau et al., 2024).

Leaders can strengthen hybrid teams by:

- Developing clinical pathways, workflows and standard work that clearly define roles and responsibilities (Oleksa-Marewska & Tokar, 2022).

- Designing criteria-based communication structures for shift handoffs, phone calls and secure messaging.

- Creating shared learning opportunities through clinical case reviews, occurrence reports and good catches.

- Ensuring sufficient technology (tablets, smartphones, telecare cameras) to support hybrid team patient care.

- Scheduling regular connection opportunities between virtual and on-site staff, such as joint meetings and touch-base sessions.

Measuring success of hybrid programs:

To evaluate the success of these leadership efforts, organizations should use:

- Leader index scores.

- Ongoing feedback to keep competencies current.

- RN turnover rates.

- Burnout levels from employee engagement surveys.

- Patient safety events including sepsis rates, mortality and other patient safety indicators.

- Nurse-sensitive quality indicators such as patient falls, catheter-associated urinary tract infections, central line-associated bloodstream infections and C. difficile rates.

- Patient flow metrics including length of stay, time to admission and discharge processing times.

- Occurrence report trends.

- Safety prevention stories.

Recent case studies show how these metrics apply in hybrid care environments. One study examined a model in which virtual nurses provided support only during shifts when staffing fell short. The presence of virtual nurses corresponded with fewer incidental overtime hours, stronger perceptions of workflow efficiency and nearly perfect compliance with timely notifications of critical lab results. Fewer rapid response and code blue events occurred when virtual nurses were on shift (Davis et al., 2025).

Another study explored a virtual nurse role in pediatric care. These nurses handled admission assessments, discharge education, and chart audits, which allowed bedside staff to focus on direct care. Nurses reported greater efficiency and continuity, while families — especially those who spoke Spanish — expressed high satisfaction with the experience. After the model was implemented, leaders saw fewer readmissions and faster discharges (Johnson-Salerno et al., 2025).

4. Recommended Resources

- AONL Span of Control White Paper

- AONL Models of Care Learning Community

- AONL Guiding Principles: Nurse Leaders' Role in Digital Transformation

- The Digital Skills Assessment Tool

- The 2023/2024 AONL Workforce Committee published "Nurse Manager Succession Planning: An Essential Workforce Strategy to Retain and Attract Current and Future Leaders," outlining a framework, process, and exemplars (AONL, 2024).

5. Appendices

Appendix A: Example Success Map

*UCHealth. (2019). Success Map Example: Talent Optimization in Partnership with Nursing.

Key Responsibilities:

As the Nurse Manager for the practice of nursing and clinical care, this position:

- Manages the business through

Examples: Financial management; legislative advocacy; performance improvement and technology. - Leads the people by:

Examples: Relationship management; shared decision making and professional governance. - Creates the leader within themself by:

Examples: Personal/professional accountability; career planning; reflective practice and delegation.

Educational and Licensure Requirements:

- License, education, and specialty certification required for role.

Essential Experiences:

- List essential experiences that are required for role success.

Examples: Management of care efficiency, throughput, and patient flow; quality, safety and patient experience best practices; create, monitor and analyze a budget; staffing management.

Future Trends:

- List important future trends that would be necessary to address and required for role success.

Examples: Changing nursing workforce (trends and shortages); rapid growth and change; increased innovation and technology; reduction of reimbursements; redesign of health care delivery models.

Key Relationships

- Identify and list key relationships required for role success.

Examples: Directors; quality colleagues; regulatory colleagues; interprofessional clinicians; professional development colleagues; medical staff leadership and providers.

Participation:

- List important groups, councils, or organizations to participate in for role success.

Examples: Patient safety; quality, and experience Groups; practice councils; professional organizations.

UCHealth Leadership Competencies:

- List organizational specific leadership competencies required for role success.

Appendix B: EAGLE Program Coaching Worksheet Template: Nurse Manager

Nurse Manager Coaching & Development Worksheet

Appendix C: EAGLE Program’s Nurse Manager

Intermediate Competency Grid, cross-referenced with the AONL Core Competencies and detailed accountability matrix.

| AONL Competency | Self | People | Fiscal | Support | Materials/Equipment | System |

| Leader Within | Engages in regular self-care; identifies personal/ professional growth needs; seeks mentorship. | Mentors charge nurses and department leaders; supports leadership succession planning. | Understands the financial impact of key departmental processes. | Supports team well-being and work/life balance. | Participates in equipment planning and resource allocation decisions. | Collaborates with interdisciplinary departments to advance clinical practice; integrates DEI into department operations. |

| Professionalism | Reflects on leadership growth; fosters a relational leadership style. | Holds staff accountable for performance; leads HR efforts; recognizes and rewards staff. | Manages and delegates FTEs, productivity, capital planning, and payroll. | Leads risk and service recovery processes (e.g., RCAs); enables professional development and PLAN involvement. | Ensures staff have proper training and tools to perform their work safely and effectively. | Drives quality improvement through QI/PI education and daily management system; contributes to SOPs and high-reliability practices. |

| Communication & Relationship Management | Contextualizes communications; practices open, inclusive dialogue. | Builds strong communication culture; ensures respectful dialogue; models and manages interprofessional relationships. | Communicates the financial impact of performance, staffing, and care outcomes. | Aligns communication with education teams to advance PLAN, VIP, and team development initiatives. | Guides communication about new technology and equipment with staff. | Facilitates communication with interdisciplinary teams (e.g., Ethics, Risk, Quality). Develops department-specific strategic communication plans. |

| Knowledge of Health Care Environment | Identifies knowledge gaps and seeks development opportunities in EBP and regulatory practice. | Ensures staff understand protocols, policies, and evidence-based guidelines. | Ensures financial alignment with nurse-sensitive indicators (e.g., falls, infections). | Guides PLAN participation; ensures team readiness for accreditation and regulatory standards. | Ensures staff are trained on digital tools; integrates emerging tech into practice. | Ensures quality and patient safety metrics are maintained; champions regulatory readiness. |

| Business Skills & Principles | Demonstrates understanding of leadership impact on operations and outcomes. | Develops strategic plans for the department; supports recruitment and onboarding with HR/TA. | Utilizes budget and productivity tools; understands and influences NOI. | Leads performance evaluations; enables growth and accountability across team roles. | Projects space planning needs; evaluates capital investments. | Creates a culture of innovation; leads initiatives that link clinical and operational outcomes with financial goals. |

6. References

American Organization for Nursing Leadership. (2024). AONL guiding principles: Nurse leaders' role in digital transformation. https://www.aonl.org/system/files/media/file/2024/06/AONL-Digital-Transformation-Guiding-Principles.pdf

American Organization for Nursing Leadership and Joslin Insight. (2023). Longitudinal nursing leadership insight survey part five: Nurse leaders' top challenges, recruitment, retention, emotional health, and workplace violence. https://www.aonl.org/resources/nursing-leadership-survey#resources

American Organization for Nursing Leadership Workforce Committee. (2024). Nursing manager succession planning: As essential workforce strategy to retain and attract current and future leaders. https://www.aonl.org/system/files/media/file/2024/02/AONL_WF_WhitePaper3_Succession_Planning.pdf

AONL Foundation. (2022). Nurse managers and front-line nurse leaders think tank. www.aonl.org. https://www.aonl.org/system/files/media/file/2024/05/2022NurseManagereBook.pdf?mkt_tok=NzEwLVpMTC02NTEAAAGYlMN7SlnEaN8Fz9AIRlLI-

American Organization for Nursing Leadership & Laudio Insights. (2024). Trends and innovations in nurse manager retention. https://www.aonl.org/system/files/media/file/2024/10/AONL-Laudio-Trends-and-Innovations-in-Nurse-Manager-Retention_0.pdf

American Nursing Informatics Association. (n.d.). Case study repository. https://library.ania.org

Bayram, A., Pokorná, A., Ličen, S., Beharková, N., Saibertová, S., Wilhelmová, R., Prosen, M., Karnjus, I., Buchtová, B., & Palese, A. (2022). Financial competencies as investigated in the nursing field: Findings of a scoping review. Journal of Nursing Management, 30(7), 2801—2810. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13671

Bernard, N. (2014). Who's next? Developing high potential nurse leaders for nurse executive roles. Nurse Leader, 12(5), 56—61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2014.01.014

Bognar, L., Bersick, E., Barrett-Fajardo, N., Ross, C., & Shaw, R. E. (2021). Training aspiring nurse leaders. Nursing Management, 52(8), 40—47. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.numa.0000758688.41934.dc

Brigstock, T., Dunn, L., Price, H., Higgins, S., & Bates, M. (2023). Developing emerging nurse leaders. Nursing Management, 54(8), 6—10. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmg.0000000000000043

Brydges, G., Krepper, R., Nibert, A., Young, A., & Luquire, R. (2019). Assessing executive nurse leaders' financial literacy level. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(12), 596—603. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000822

Burkoski, V. (2019). Nursing leadership in the fully digital practice realm. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership, 32(SP), 8—15. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2019.25818

Chan, M. (2022). Nurse manager succession planning. Nursing Management, 53(10), 35—41. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.numa.0000874444.59805.67

Clipper, B. (2024). Implementing the activate virtual nursing framework™. Nurse Leader, 22(6), 676—680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2024.06.007

Danner, C. and Weiss, R. (2024). Building the Financial Toolkit for Today's Nurse Leader. ACHE Blog. https://www.ache.org/blog/2024/building-the-financial-toolkit-for-todays-nurse-leader

Darling, T. (2024). Leader inspired work: Insights and tools by and for healthcare managers. Laudio Insights.

Davis, J., Oster, C. A., Bruckner, A. A., Griesheim, G., Eastman, S., Virden, M. J., Yates, N., Madone, A. C., & Capra, N. (2025). Intermittent virtual nursing: A contingency staffing plan to support clinical nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 55(6), 355—365. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001588

Desarno, J., Perez, M., Rivas, R., Sandate, I., Reed, C., & Fonseca, I. (2021). Succession planning within the health care organization. Nurse Leader, 19(4), 411—415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2020.08.010

Ficara, C., Veronneau, P., & Davis, K. (2021). Leading change and transforming practice. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 45(4), 330—337. https://doi.org/10.1097/naq.0000000000000497

Ghidini, J., Williams, E., & Bilskis, S. B. (2024). Investing in novice nurse managers. Nurse Leader, 22(5), 536—542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2024.07.003

Geisinger. (2018—2021). Nursing annual reports [Internal publications].

Grubaugh, M. L., Warshawsky, N., & Tarasenko, L. (2023). Reframing the nurse manager role to improve retention. Nurse Leader, 21(2), 195—201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2022.12.013

Hahn, J., Galuska, L., Polifroni, E., & Dunnack, H. (2021). Joy and meaning in nurse manager practice. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 51(1), 38—42. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000964

Harper, M. G., & Maloney, P. (2022). The multisite nursing professional development leader competency determination study. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 38(4), 185—195. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnd.0000000000000836

Hincapie, M., & Costa, P. (2024). Fostering hybrid team performance through inclusive leadership strategies. Organizational Dynamics, 53(3), 101072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2024.101072

Huston, C. (2008). Preparing nurse leaders for 2020. Journal of Nursing Management, 16(8), 905—911. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00942.x

Johnson-Salerno, E., Rodriguez, S., Fausnaugh, J., Pillow, J. B., Haut, C., Carpenter, A., Johnson, N., & Mericle, J. (2025). Implementing a virtual nurse model pilot in a pediatric hospital. Journal of Nursing Administration, 55(6), 335—342. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001585

Keith, A. C., Warshawsky, N., Neff, D., Loerzel, V., & Parchment, J. (2020). Factors that influence nurse manager job satisfaction: An integrated literature review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(3), 373—384. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13165

Kennedy, M., & Moen, A. (2025). Nurse leadership and informatics competencies: Shaping transformation of professional practice. In Studies in health technology and informatics. IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-738-2-197

Krivanek, M. J., Colbert, C. Y., Mau, K., & Distelhorst, K. (2023). An innovative assistant nurse manager residency program focused on participation, satisfaction, promotion, and retention. Journal of Nursing Administration, 53(10), 526—532. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001329

Lawson, C. (2020). Strengthening new nurse manager leadership skills through a transition-to-practice program. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(12), 618—622. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000947

McFarlan, S. (2020). An experiential educational intervention to improve nurse managers' knowledge and self-assessed competence with health care financial management. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 51(4), 181—188. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20200317-08

McGarity, T., Reed, C., Monahan, L., & Zhao, M. (2020). Innovative frontline nurse leader professional development program. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 36(5), 277—282. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnd.0000000000000628

Morin, A., King, S., Glennon, S., & Landers, K. A. (2024). Grounded in proficiency: A crosswalk between nurse leader digital transformation guidelines and core competencies. Nurse Leader. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2024.12.005

Nghe, M., Hart, J., Ferry, S., Hutchins, L., & Lebet, R. (2020). Developing leadership competencies in midlevel nurse leaders. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 50(9), 481—488. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000920

Oleksa-Marewska, K., & Tokar, J. (2022). Facing the post-pandemic challenges: The role of leadership effectiveness in shaping the affective well-being of healthcare providers working in a hybrid work mode. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14388. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114388

Parchment, J., Galura, S., & Warshawsky, N. (2024). Supporting the role transition of interim nurse managers. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000001387

Qin, S., Zhang, J., Sun, X., Meng, G., Zhuang, X., Jia, Y., Shi, W.-X., & Zhang, Y.-P. (2024). A scale for measuring nursing digital application skills: A development and psychometric testing study. BMC Nursing, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02030-8

Ramseur, P., Fuchs, M., Edwards, P., & Humphreys, J. (2018). The implementation of a structured nursing leadership development program for succession planning in a health system. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 48(1), 25—30. https://doi.org/10.1097/nna.0000000000000566

Scortzaru, M., DeVolt, M., Ogilvie, L., Luttrell, J., Mangum-Williams, M., & Parazin, J. (2024). Adaptive leadership in virtual nursing environments. Nurse Leader, 22(5), 501—505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2024.05.008

Sensmeier, J., Anderson, C., & Shaw, T. (2019). Empowering nursing leadership for digital health transformation: The role of nursing informatics. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 43(4), 306—313. https://doi.org/10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000370

Stagg, C., Turner, B., Bigby, E., & Jensen, J. (2023). Effects of leader empowerment: Implementing a frontline nurse leadership council. Nurse Leader, 21(2), 207—212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2022.04.011

Suby, C. (2025). Labor Management Institute 34th Perspectives in Staffing & Scheduling (PSS™) Annual Survey of Hours Report©.

Suby, C. (2023). Operational excellence & effective staffing strategies. Labor Management Institute. https://www.LMInstitute.com

Tamera J. Larsen-Engelkes, MSN, RN, NE-BC, CNO, Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center. Summary of ERAS implementation outcomes, 2025.

Titzer, J. L., Shirey, M. R., & Hauck, S. (2014). A nurse manager succession planning model with associated empirical outcomes. Journal of Nursing Administration, 44(1), 37—46. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000019

Watkins, A., Wagner, J., Martin, C., Grant, B., Maule, K., Resh, K., King, L., Eaton, H., Fetter, K., King, S. L., & Thompson, E. J. (2014). Nurse manager residency program: An innovative leadership succession plan. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 33(3), 121—128. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCC.0000000000000036

Waxman, K., & Knighten, M. (2023). Financial & business management for the Doctor of Nursing Practice (3rd ed., pp. 111—154). Springer Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826160164

7. Committee Members

Chair:

Diane Regan, DNP, RN, associate chief nursing officer, Tufts Medicine, Lowell General Hospital, Lowell, Mass.

Committee Members:

Noreen Bernard, EdN, RN, CNO, chief nursing officer, UCHealth Parkview Health System

Martha Grubaugh, PhD, RN, research nurse scientist, UCHealth

Tamera Larsen-Engelkes, MSN, NE-BC, chief nursing officer, Avera Health

Jennifer Moberg, DNP, RN, vice-president of Emergency Services, ChritianaCare

Karla Schroeder, DNP, RN, chief nursing officer, Emory Ambulatory Patient Care, Emory Healthcare

Amy Rosa, DNP, RN, chief nursing informatics officer, Sentara Health

ChrysMarie Suby, MS, RN, president and chief executive officer, Labor Management Institute, Inc.

Tamera Sutton, MSN, RN, vice president of clinical products delivery, Press Ganey

Nora Warshawsky, PHd, RN, nurse scientist, Press Ganey Associates

AONL Staff:

Lori Wightman, DNP, RN, regional chief nursing officer, Mount Carmel Health System

Genevieve Diesing, compendium editor, Diesing Communications, Inc.