Creating More Diverse C-Suites: From Intention to Outcomes

Over the past year, nurse executives have been called upon to respond to dramatic clinical, economic and professional disruption, including resource and workforce shortages because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The greater incidence and less favorable clinical outcomes of the pandemic on minority populations, coupled with concurrent racial unrest, have coalesced to underscore major fault lines within our health care system. These recent events have highlighted the disparities in clinical outcomes for diverse populations as well as the value of diverse executive leaders in health care.

Diverse leaders bring a unique understanding of cultural differences that impact health, values and beliefs in addition to the experience of race in America. The addition of a diverse perspective to leadership teams can help organizations improve racial health disparities and employee and patient experience. In order to create organizations that effectively address the first issue—disparity of clinical outcomes—successful organizations must create diverse executive and senior leadership teams reflecting the populations served and the cultural dynamics of the current and emerging workforce.

Despite a quarter century-plus of monitoring leadership diversity in health care by national professional organizations, little progress has occurred. While women represent 66% of the health care entry-level workers, they hold only 30% of the C-suite positions, while minority women hold only 5% of C-suite positions in health care (Berlin et al., 2020). Are these statistics evidence of discrimination and racism within our health care system? Further, what barriers do diverse leaders face in obtaining, maintaining and advancing their leadership careers and what can be done to eliminate or overcome inequalities that do exist?

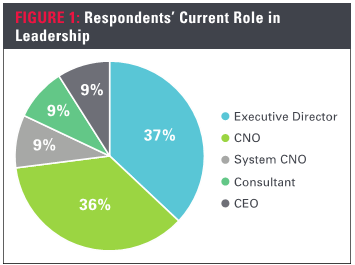

To answer these questions, the authors of this article designed and conducted a survey, fielded in 2018 and 2019, to gain a better understanding about barriers to career advancement and recommendations for future leaders by sampling successful diverse nursing executives and senior leaders. The respondents (N=50) represented diverse leaders holding prominent positions in health systems, academic medical centers, hospitals and educational institutions (Figure 1).

Ninety percent of the respondents stated that they had “experienced barriers to career advancement due to their race.” One of these highly successful nursing leaders described her experience of others assuming she was a “patient transporter because of (her) race”, while another described being told by members of the board, “you will not last in your role because they don’t like Black people here;” yet another diversity candidate was told that while she had interviewed well, “maybe it’s just your face, but the CEO doesn’t think you would fit in here.”

Of those who experienced racism, 100% believed the barriers become increasingly prevalent when advancing to the executive level. One respondent noted, “with the sought-after jobs” the experience can be “tortuous.” While diverse leaders report that the proper education and credentials are essential, more than a few stated that minorities must far exceed the required standards for education, credentials and experience than their majority race counterparts. One respondent explained, “Meeting the standard is not good enough, you must exceed the standard to be accepted.” In fact, many others mirrored this sentiment. For example, respondents recounted instances where white candidates with less experience were selected over a more qualified diverse candidate. As one recalled, “I have applied for positions for which I was qualified and had the necessary experience and the job was given to someone with less preparation, skill, and experience.” Another shared, “I have been singled out for doing extraordinary work but overlooked for advancement. It is almost like I am invisible.”

These results were similar to a qualitative study (Paraway, 2017), that found “African American and Black nurses” were perceived to “lack credibility, competence and respect” providing further evidence that “organizational racism exists.”

Different types of racism

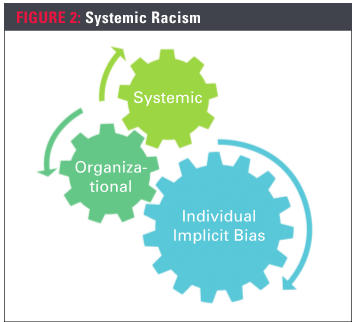

The experiences cited by survey respondents clearly identified barriers to their career advancement. This begs the question of whether this is due to racism within our health care organizations. It is important to understand that racism takes on different forms and is expressed in a range of severity, from unintended discrimination to antagonistic racial or ethnic aggression. It is important to note, however, that both individual and organizational racism may be unintentional.

On a personal level, everyone has implicit bias which develops as a normal part of our neurological anatomy and life experiences. It influences our world view and decision-making often, at an unconscious level. We are hard-wired to favor what is familiar and to feel less safe with the unfamiliar. We tend to like people who look, think and act like us, which can result in unintentional discrimination and prejudice. In fact, the barriers faced by minority sub-groups and the effects of organizational racism are often invisible to the majority white culture.

At the organizational level, structured racism can occur when policies, practices and traditions are designed to work better for the majority culture than for people of color. If the leadership team of an organization is all from the majority culture, it is only natural that the systems created will favor the majority values and perspectives. Given that health care leadership, as mentioned, has been dominantly comprised of individuals from the white majority culture, the executive perspective is representative of that same majority culture. This allows little space for the values and perspectives of those outside the majority culture, namely people of color, to be expressed, heard and honored, not only in our health care leadership, but in the populations we serve. Even as an organization tries to become more inclusive, the barriers and obstacles that need to be changed are frequently not obvious to the majority leaders.

Systemic racism occurs when there is a long history and current reality of organizational racism across all institutions combining to create a system that negatively impacts communities of color. Given our lack of success in increasing the diversity among health care executive teams, we can safely say that, despite good intentions, health care suffers from systematic racism (Figure 2).

Barriers to career advancement

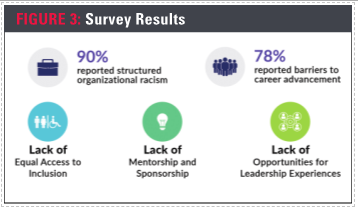

In an effort to understand the obstacles to advancement experienced by diverse nurse leaders, the survey asked respondents to identify what they perceived to be the top three barriers to career advancement (Figure 3). The responses highlighted three major areas:

- Unequal access to opportunities

- Absence of mentorship and sponsorship

- Lack of opportunities for leadership experiences

Numerous examples of unequal access to opportunities were described. Many respondents referred to a lack of inclusion in the inner circle. One respondent observed, “Executive-level positions depend on who you know and often we are not included in the inner circle and may not even be unaware that an opportunity is available.” Another remarked, “Individuals that move to the executive level position typically have [professional] connections that help propel their career. Minorities for the most part do not have these connections.”

In addition to exclusion from inner circle knowledge, respondents believed there was frequently an absence of a fair and equitable selection process. One respondent described the situation from the viewpoint of being a member of the selection committee. “I have participated in many search committees. Even if there is conversation about keeping an open mind to a diverse pool of candidates, the results seldom occur.” The selection team “has to make a commitment to hire someone that doesn’t look like them, think like them and has had different experiences.”

The second most often identified barrier to advancement was a lack of mentorship. “You have the right qualifications, but you do not have leaders from your race to facilitate your advancement because they are not in positions of power.” Given the scarcity of minorities in executive leadership roles, respondents indicated that it is important to have majority race leaders who were willing to act as mentors to emerging diverse leaders. While many respondents credited mentors as important to their career success, others found it challenging to build those relationships. “It is difficult to build relationships with people who will mentor you,” said one respondent, while another noted, “Minorities are under a microscope and organizations will not take chances on you.” Having a mentor from the majority culture was perceived as especially beneficial because white leaders can assist a minority professional to “learn the rules of engagement and navigate the nuances of the cultural and political systems.”

The third area that respondents selected as a barrier to advancement was access to leadership experiences and the chance “to be visible and showcase your talents.” Many identified this as a deficit that occurs during early to mid-career. “I felt that the organization could not see me as a viable candidate for executive roles.” Diverse professionals are often not given the opportunity to work beyond their position in a way that promotes visibility and builds confidence and experience. “Many [diverse] nurses have limited networks, few mentors and no meaningful avenues of mutual support” (Wesley & Dobal, 2009). Diverse nurses fail to advance beyond clinical and middle management positions, looking in anticipation through a glass ceiling to an unattainable goal (Qaabidh et al., 2011).

Organization leaders must examine who is recommended or selected to make presentations, serve as chair councils, attend conferences or serve in interprofessional roles. These mid-career experiences are fundamental to moving beyond the scope of an existing role by interacting with others across disciplines and across the organization. They also offer the opportunity to be recognized and to showcase skills to new stakeholders. According to one respondent, the lack of these mid-career opportunities often results in a diverse candidate’s having a “slimmer resume” than his or her counterparts.

Moving beyond racism

Survey respondents shared numerous recommendations to promote equity and inclusion in health care organizations and to develop more diverse leadership teams

Create safe spaces for self, organization and systems

- Establish safe spaces for team members to learn more about themselves and one another as a way to activate a culture of belonging and subsequent safety among employees.

- Convene forums for authentic dialogues on race, racism and injustice.

- Understand terminology, concepts and practices related to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) standards and expectations within the institution.

- Speak candidly and learn about the challenges of achieving diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging in both the workplace and our communities at large.

Promote equity

- Provide the same things to all people to achieve equity and provide what each person needs.

- Teach colleagues about implicit bias.

- Engage in respectful dialogue and build trust to understand needs. Devise new approaches and tools that allow everyone to contribute to their fullest.

- Examine and redesign policies, procedures and practices.

- Take bold steps to eliminate favoritism, structure, policies and practices that perpetuate organizational racism.

Reassess your recruitment and advancement processes

- Prepare your organizational culture to embrace diversity and inclusion, creating an environment that will welcome diverse leaders.

- Open your mind to many possibilities and people; do not appoint “someone you know.”

- Develop measurable criteria to drive the selection process. Do not base such important decisions on likability.

- Examine and redesign policies, procedures and practices.

- Think more broadly about leadership; consider potential and ability vs. pigeonholing people based on their current roles.

Require a diverse pool of candidates from your search firm

- Consider a blind review of resumes in initial screening.

- Insist on candidates that bring quality, competency and diversity.

- Develop measurable, objective criteria for success in the role.

- Use candidate interview questions specific to the criteria for success.

- Create an evaluation tool based on objective, measurable factors.

- Provide consultation to prepare the search committee and guide the internal process.

- Make decisions based on evaluation data and objective interviewer feedback.

Progress from mentorship to sponsorship

Mentors are invaluable in proving career guidance. Sponsorship, also called intentional inclusion, describes a more formalized relationship that is focused on the advancement of the protégé. Sponsors open doors and provide access to relationships and opportunities. Three ways to promote sponsorship:- Create guidelines around sponsorship to ensure that cross-demographic sponsorships are common.

- Develop a strategy to encourage a culture of sponsorship.

- Ensure that employees from underrepresented backgrounds and their achievements are visible and celebrated at rates at least as high as those from well-represented backgrounds.

Create infrastructure to monitor and track progress

Expand, diversify and track the effectiveness of mid-level professional development programs. Assess the results of these outreach programs to determine what is working and what is not effective.Dismantle racism – become anti-racist

Don’t get stuck in the fear zone; move to the learning and growth zone (Kendi, 2019). Apply a racial equity lens everywhere, including:- Patient satisfaction

- Employee engagement

- Access and wait times

- Quality outcomes

- Attendance policy

- Succession planning/promotions

Next steps

As an informed executive, you must assess the environment within your current organization. Does it promote fair and equitable processes? Do you engage one on one with diverse nursing leaders? Promoting growth, advancement and inclusion are the first steps towards achieving increased diversity in health care leadership. Given the challenges of implicit bias, be intentional in creating inclusive environments and be extra vigilant when developing recruitment, leadership development and career advancement processes.

When you feel like you don’t have the energy to commit, to partner, to lead from the bedside or when you grow weary, remember the words of Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“All labor that uplifts humanity has dignity and importance and should be undertaken with painstaking excellence.”

REFERENCES

Berlin, G., Darino, L., Groh, R., & Kumar, P. (2020). Women in healthcare: Moving from the front lines to the top rung. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Healthcare%20Systems%20and%20Services/Our%20Insights/Women%20in%20healthcare%20Moving/Women-in-healthcare-Moving-from-the-front-lines-to-the-top-rung.pdf

Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an Antiracist. One World.

Paraway, Y. (2017). A phenomenological Inquiry on barriers experienced by African-American nurses denied leadership positions. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Phoenix]. Proquest Dissertations Publishing.

Qaabidh, L., Gulstone, J., George-Jackson, G., & Wesley, Y. (2011). Executive leadership among Black nurses: A necessity for overcoming healthcare disparities. Journal of Chi Eta Phi, 55(1), 2-6.

Wesley, Y. & Dobal, M. (2009). Nurses of African descent and career advancement. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25(2), 122-126.

About the Authors

M. Jane Fitzsimmons, MSN, RN, is executive vice president, executive search services, Kirby Bates Associates, Orlando, Fla.

Angelleen Peters-Lewis, PhD, RN, FAAN, is the chief operating officer and patient care services chief nurse executive, Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis.